Thinking Our Way Out of the Darkness

September 16, 2015

"The most significant gift our species brings to the world is our capacity to think. The most significant danger our species brings to the world is our inability to think with those who think differently. It is clear that to stay competitive in our global economy, we must learn how to think collaboratively and innovatively. But if you have ever sat through a mind-numbing meeting or tried to influence a colleague's view on a project or had a recurring argument with a family member or struggled to participate in a community project, you have recognized that most of us actually don't know how to think well together. We take for granted that intelligence occurs within our own minds. We don't realize that it also occurs between us. What keeps us from tapping into that intelligence and communicating effectively is that most of us don't know how to think with people who think differently than we do. We habitually misread people and therefore miscommunicate with them."

Farmers used to think that it was

Farmers used to think that it was

in the nature of chickens to peck at

one another,

that they were basically loners, unsocial animals that couldn’t mingle without being nasty. On some farms, their beaks were clipped, but this only made it more difficult for the chickens to eat—which made them hungrier, so they pecked at themselves and one another even more. Then a chicken farmer somewhere noticed something exquisitely simple that changed everything: chicken coops were dark, and the absence of light was what was

causing the chickens to peck at themselves and one an-other. As soon as that farmer introduced a light source into his coops, his chickens stopped pecking—it was as simple as that. People are not all that different. When we don’t know what our minds need to think well together, we are like chickens pecking around in the dark. This isn’t as far afield as it might seem: When we are communicating and thinking well together, our faces actually “light up.” When our minds don’t get enough light, our thinking breaks down and we begin to peck at one another and ourselves.

Humans can no longer afford to think in division and darkness. Collaborative intelligence is the light that is necessary for our individual and collective survival. We have no choice now but to think together.

Great Minds Don’t Think Alike—But They Can Learn To Think Together

“There is a new story waiting for our voice. It is the story of human possibility, of what people are capable of when we come together. Many of us carry this story inside but are afraid to speak it. We tell ourselves we’re crazy. But in fact we represent the new sanity—the ideas and practices that can create a future worth living.” — Meg Wheatley

The most significant gift our species brings to the world is our capacity to think. The most significant danger our species brings to the world is our inability to think with those who think differently. It is clear that to stay competitive in our global economy, we must learn how to think collaboratively and innovatively. But if you have ever sat through a mind-numbing meeting or tried to influence a colleague’s view on a project or had a recurring argument with a family member or struggled to participate in a community project, you have recognized that most of

us actually don’t know how to think well together.

We take for granted that intelligence occurs within our own minds. We don’t realize that it also occurs between us. What keeps us from tapping into that intelligence and communicating effectively is that most of us don’t know how to think with people who think differently than we do. We habitually misread people and therefore miscommunicate with them. We blame and belittle one another and ourselves. We haven’t been taught to notice the effect we have on someone else or to fluidly shift the ways we communicate to accommodate them. We are accustomed to considering diversity through the lens of race, gender, and culture, but most of us are unaware that there is also a range of differences in how we think—intellectual diversity.

We celebrate diversity in sports and the arts, but even the relatively recent concept that humans have “multiple intelligences,” as articulated by developmental psychologist Howard Gardner of Harvard, is of very limited use, because we haven’t been trained to value and utilize those diverse capacities. Peter Senge, author of The Fifth Discipline, estimates that the IQ of a group can actually drop by more than 30 percent compared to the IQ of individuals in the group.

Never have we needed collaboration more. We are living in an age of complexity, chaos, and collapse. Every significant conversation between us seems to be a tug-of war between polarities. Black or white. Red or blue. We don’t know, or have forgotten, how to think together about the possibility of purple. We tear ourselves apart with the mistaken belief that we must decide between two opposing forces: independence or interdependence. We believe we have to either stand on our own two feet as rugged individuals making a mark and achieving recognition or sacrifice our uniqueness in order to accommodate a larger whole—a company, a family, a community.

Imagine that you are holding a rope, one end in each hand, and pulling it in opposite directions. Who are the adversaries or adversarial forces in your life right now that pull you apart? Most minds, most leaders, and most organizations are stuck in this position. The harder we pull away from one another, the more tightly stuck we become. The only way to resolve this, in fact, is to take the pressure off and allow the ends of the rope to bend toward each other, asking the question: “How can the real needs of each of these opposing forces be met?” In this way, we free our minds to think together about how to “make ends meet” until we form a circle.

Many of the barriers keeping us apart are actually optional, present only in our minds. When our lives depend on it, we draw on the innate hardwiring we have to connect. Remember the first days after September 11? As a society, we experienced a visceral longing to connect, to help, to offer whatever we had—prayers, talents, resources—to those most directly affected. We instantly changed our habitual individuated ways of thinking. What appeared to be separate and polarized human needs came into balance, if only for a short time.

We take for granted that intelligence occurs within our own minds.

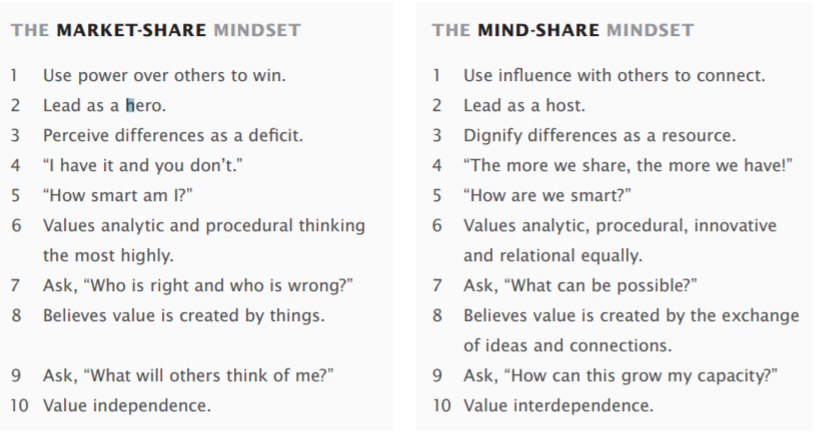

Shifting From A Market-Share to a Mindshare Mentality

We are living in a hinge time. We have been educated for a time that no longer exists. We are confronted with vastly different challenges than the ones of our predecessors, who were taught how to be right but not how to be effective with other people. Most of us have been trained for a Market-share economy. We are now entering a Mind-share world. No longer just dealing with analytic and procedural problems that require rational solutions, we’re being asked to think together in ways that are innovative and relational. We must work across continents, cultures, time zones, and temperaments. People who have never met each other are being forced to come

up with breakthrough solutions to ridiculously complex problems.

In the Market-share way of thinking, value is determined by shortage—I have it and you don’t. Objects are valued according to their scarcity, like diamonds. Market-share mentality solves problems by asking our minds to think practically, analytically, and procedurally. We break down challenges into small pieces and arrange them neatly in sequential order, hoping the solution will make itself apparent. A question is asked and our brains shoot back an answer: Ready, Fire, Aim. We focus our individual and collective attention on deficits—cognitive, emotional,

and financial.

When we think this way, we bifurcate. We get stuck at the ends of the rope: either I’m right or you are. Select one answer or the other. A leader is the hero who has clawed his way up the ladder of success and accumulated the most power over others. Success is measured in assets accrued. Former U.S. IKEA CEO Goran Carstedt posits that we are, in fact, moving into a time of growth, where wealth is carried by ideas and relationships more than transactions. Wealth is created and carried by ideas and relationships more than transactions. When things carry value, if I have one and give it away, I lose something. But when ideas carry value, everything is turned upside down. When you have a good idea and I have a good idea and we exchange them, you walk away with two new ideas and I also have two new ideas. The more we share, the more we have. Our capacity to generate, share, and enact ideas becomes what is most valuable.

A Mind-share mentality necessitates that we learn to use influence with others rather than power over them. This is especially crucial now because in the age of rapidly formed “Velcro teams” where people work together remotely for a short period of time, across continents, it is influence, not power, that is needed to get breakthrough work done. Mind share also requires developing the capacity within to be influenced by others. In this way, leadership becomes a verb, to host, rather than a noun, the hero. Ultimately in a Mind-share world, the ones who are most flexible in their thinking will be the ones who have the most influence.

A Market-share mentality requires that we answer questions quickly and expertly. A Mind-share mentality requires that we know how to ask the kinds of questions that open our own and others’ minds to new possibilities. Market share determines who is right and who is wrong. Mind share asks what is possible. This kind of inquiry encourages the brain to wonder. It is wonder that creates the fertile and generative ground for ideas to generate. It is wonder that bridges seemingly opposing thoughts into a new truth.

Daniel Pink in his bestselling book A Whole New Mind wrote that we can’t solve today’s and tomorrow’s problems with yesterday’s ways of thinking. Because most of us have only been educated in the Market-share mentality, our problem-solving abilities, our communication skills, and our capacity to bend that rope and bridge differences haven’t evolved quickly enough to sustain us. We have been taught that the one who pulls hardest wins. We have been trained to use thinking strategies that result in one side or the other losing. How many times have you experienced someone in a meeting trying to control the thinking by needing to be right? How many times have you noticed a leader attempting to resolve differences by eradicating them? How often have you noticed people you work with attempting to controlling another person or retaliate by getting even or silently withdraw their intellectual resources? Of course, you yourself may have been trained to use the very same strategies. They are essential to a Market-share mentality that uses power over others: power to provoke, protect, procure, preserve.

A Mind-share mentality requires that we maximize our capacity to generate, distribute, and enact ideas. Value lies in the process of thinking itself, particularly thinking with others who think differently than you do. In our experience as advisors to global CEO’s and senior leadership teams, we’ve discovered that it is essential for each person to understand the contribution he or she makes, as well as recognize the talents and thinking styles of others. Leaders need to know how to create a bridge between people who think differently. Most of us have been trained for a Market-share economy.

Ten Things You Can Do to Shift from a Market-share to a Mind-share Mindset

Collaborative intelligence (CQ) is a critical component of a Mind-share mentality, because it allows you to recognize the expertise that is present and also what is missing. Here’s how it could work: imagine a 45 minute phone call with a group of people you have never met from around the world. Each person introduces him or herself and shares his or her thinking talents, blind spots, and their most effective way to receive communications. No second-guessing needed. By the time the introductions are complete, you have, in effect, an operating manual that helps you understand the differences in how the people around you think. As the meeting progressed, you could easily avoid counterproductive assumptions that you would normally attribute to personality. Without understanding each other’s unique mental talents and particular patterns of thinking, we are like the chickens pecking at each other in a dark cage, trying to prove who is at fault.

In a study on collaborative advantage published in the Harvard Business Review, Rosabeth Moss Kanter observed thirty-seven companies and their partners from eleven parts of the world. She and her associates found that North American companies, more than others, “take a narrow, opportunistic view of relationships” and “frequently neglect the political, cultural, organizational, and human aspects of the partnership.” She concluded that collaborative alliances “require a dense web of interpersonal connections and internal infrastructures.”

Breakthrough Practice: Thinking Yourself Alive

We are used to seeing what we expect to see, hearing what we expect to hear, and doing what we expect to do. However comforting, these habits of thinking can make us numb and limit our potential. They offer ease without challenge, reassurance without insight, and certainty without imagination. In our work helping senior global leadership teams think well together, we realized that most breakdowns and breakups are a result of habitual thinking and most breakthroughs are a result of non-habitual thinking. We needed, therefore, to offer as many multi-sensory and non-habitual ways to help people who think differently think together. We first introduced breakthrough practices in the leadership seminars we facilitated with Peter Senge at the Center for Organizational Learning at MIT’s Sloan School of Management. Because they often included learning through the body, some people thought they were the “exercise” portion of the program and wanted to know when they were going to get to the “real stuff.” As they experienced the practices, however, they began to make very interesting discoveries,

such as where in their bodies they held themselves back from receiving someone else’s influence or how it felt physically to depend on others and also to have others depend on them.

These leaders became aware of how they habitually used power rather than influence to meet challenges. We could almost hear the doors of their minds creaking open. Conflict with colleagues turned into a subject of curiosity rather than a problem to be avoided. It became obvious that physically experiencing a new understanding made the concept readily accessible. “Of all the stuff I learned about systems thinking and mental models,” wrote the head of R&D at a large telecommunications company, “nothing was so directly useful to me as the embodiment breakthrough practice that helped me become aware of what happens to me physically during a meeting.”

Here’s one that will help you explore the value and difficulties of thinking with someone who thinks differently than you. Physicist, black-belt martial artist, and founder of psychophysical re-education Moshe Feldenkrais originated it.

1. Fold your hands by interlacing the fingers as you have done habitually since you were a well-behaved young child. 2. Now bring your attention to the way you are doing this. Is the right thumb on top of the left or the left on top of right? 3. Next, unfold your fingers and refold them in the opposite, non-habitual way (i.e., if right was on top of left, put left on top of right, or vice versa). 4. Go back and forth between the two ways while asking yourself: Which feels most comfortable? Which feels most awkward? Which feels most secure? Which one helps you be the most aware of the spaces between your fingers? Which helps your hands feel the most alive to you?

When we learned this practice, we were amazed to discover that what was awkward could in fact make us feel more aware and alive. We are trained to avoid feeling awkward at all costs. To feel secure and comfortable we often live within a box of habitual thinking. Remember, the most significant gift our species brings to the world is our capacity to think. The most significant danger our species brings to the world is our inability to think with those who think differently. Next time you are about to cross the red line and enter the danger zone, you can repeat this practice a few times while asking yourself, “How can we collaborate so both of us move forward?” The responsibility for learning more about how to grow collaborative intelligence is in your hands now.