Unfear for Wellbeing

Fear itself is not the problem.

Negating or ignoring fear can get us hurt or worse. But becoming overly fearful is detrimental to our growth and development. And that holds true for both individuals and organizations. The solution is to tranform our relationship with fear. Fear itself is just an emotion, which is neither good nor bad. It is necessary to understand the underlying message beneath our fear and to make different, more positive choices in the face of that fear.

Whenever we ask our clients to recall a time when they were part of a high-performing team, they usually tell stories about intense, hard-working environments where team members frequently had constructive debates about different ideas and ways to move forward. They talk about groups that didn’t let relationship conflict or stress get in the way of their work and situations in which they could have honest disagreements with their colleagues without any fear that the colleague would take their comments personally. In short, they describe a team that could effectively engage in challenging conversations about performance, attitude, alignment, direction, and strategy. These conversations promote well-being within a team. If team members feel that they can’t address an issue with their colleagues, they will suppress their emotions, obsess over them, and let them fester and grow. This poisons team members, creates unproductive stress, and makes it more likely for work to impact them when they get home because they can’t process and let go of whatever is bothering them. Alternatively, they might have that difficult conversation, but in a clumsy, aggressive manner. When they do that, they merely spread the poison to the rest of the team.

These conversations depend on trust. When there is too much fear in a team—either between colleagues (i.e., one person is afraid of another) or within oneself (i.e., I’m afraid that I will fail)—it completely destroys trust. The good news about trust and difficult conversations is that they create a virtuous cycle, a positive-feedback loop, whereby difficult conversations build trust, and the more trust there is within a team, the more effective it becomes at difficult conversations.

Teams that operate on fear prevent these conversations from taking place. For example, we once worked with the leadership team of a global leader in healthcare. Even though the company was a leader, its revenue was stalling, and the board didn’t like the company’s prognosis. The board hired a new CEO, who was a turnaround specialist, to help get the company back on track. Right after becoming CEO, he implemented a series of unilateral actions and replaced almost 70 percent of the leadership team. If something went wrong in any department, he would fire its leader immediately. In doing so, he created a culture in which the leadership team couldn’t make any decisions without his direct approval.

In fear for their jobs, nobody questioned the CEO or offered new ideas for improvement (in other words, they didn’t have any difficult conversations). The senior leaders didn’t trust the CEO to have their backs if a risk didn’t pan out, so nobody took any risks. In the short run, everyone worked so hard that the CEO managed to turn the company around. He took this as proof of concept and became more entrenched in his way of operating. As time went on, because nobody engaged in difficult conversations, the business stagnated again. This only confirmed the CEO’s belief that he couldn’t depend on his team, so he drove them even harder. He started speaking negatively about his team members behind their backs, leading to an even greater breakdown of trust. This pulled the team and the entire organization into a downward spiral. It gummed up decision-making, created silos, and resulted in costly strategic mistakes. The CEO felt a great degree of fear and pressure to turn the organization around and pushed that down the corporate ladder. Eventually, it hurt performance so much that, as we write this, the board is considering letting the CEO go.

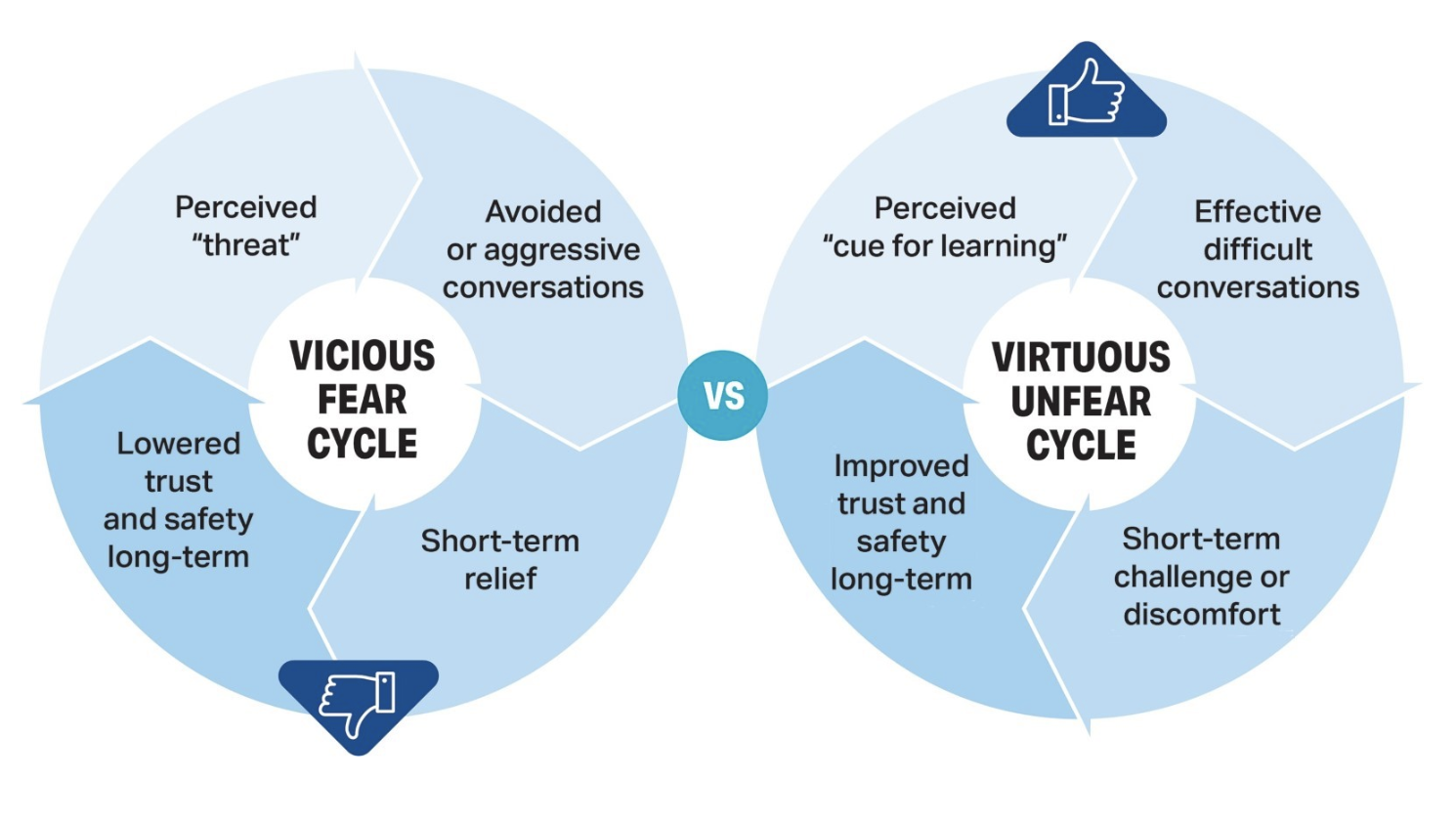

We call this pattern the CEO fell into “the vicious fear cycle,” where someone reacts to a perceived threat with aggression or apathy, which lowers the degree of trust within the organization and makes it more likely for others to take the same approach (Figure 1.1). The cycle often goes unnoticed because the aggressive/apathetic responses work in the short term. But they erode results over time. However, when we unfear, we flip this cycle. Threats become opportunities for learning and growth, the team has effective difficult conversations, and this bolsters trust and leads to more effective conversations in the face of new cues for learning.

FIGURE 1 .1 Vicious fear cycle versus virtuous unfear cycle

Over a long-enough period of time, fear that causes individuals and teams to show up in a less-than-ideal way will eventually show up in a company’s bottom line.

There are three primary reasons this happens: (1) fear leads to poor long-term strategy, (2) fear creates an environment that prevents a company from developing an inclusive, diverse culture, and (3) fear massively reduces employee engagement.

POOR LONG-TERM STRATEGY. When organizations and business leaders are in the throes of fear, they engage in a range of reactive responses that are ineffective. Some common reactive choices include:

- Burying your head in the sand. Organizations avoid acknowledging adversity and hope that it will go away. Traditional car manufacturers did this in response to the disruption created by Tesla. When Tesla came into the market, traditional manufacturers dismissed it as a sideshow and invented countless arguments on why the electric motor would never replace the combustion engine. In 2021, Tesla’s market capitalization as $710.08 billion, which was larger than the next top five car makers—Toyota, Volkswagen, Daimler, General Motors, and Build Your Dreams (BYD)—combined.

- Throwing money at the problem. When business leaders do this, they are trying to find solutions before they really understand the problem. They never take the time to question the mindset or thinking that actually caused the problem, instead burning through cash to solve the issue as it appears on the surface. One of the furnaces that companies pitch the most money into is digital transformation. According to the International Data Corporation, global spending on digital transformation will reach about $2.3 trillion in 2023.1 Yet a 2020 Boston Consulting Group (BCG) study2 shows that 70 percent of digital transformations fail to produce their desired objective. According to the study, the determining factor in their success or failure is the “people dimension,”3 stating that “organizational inertia from deeply rooted behaviors is a big impediment.”4 In our experience, this inertia comes from a dysfunctional relationship with fear.

- Cutting heads. Leaders often see head-count reductions as a silver bullet to deliver cost savings. Yet, as Richard Barrett shows in his book, Liberating the Corporate Soul,5 fewer than half the companies engaging in such reengineering efforts see an improvement in short-term profit and fewer than a third see productivity improvement. The reason so many of these change efforts fail to produce the desired effect is that management doesn’t understand and acknowledge the fear these efforts create. The fear generated by poorly handled layoffs tears at the social fabric of a company, sabotages trust, and diminishes collective productivity and creativity.

- Making a flashy acquisition. Often, when a large organization fears that it lacks the capacity for innovation, it tries to solve the problem by buying a radical, forwardthinking, young firm. The senior leaders of the acquiring company, often out of fear that they will lose their jobs to the partners at the acquired firm, work so hard to assimilate the new firm that they destroy what made it unique and radical in the first place.

- Starting a flavor-of-the-month transformation effort. Usually these are the pet projects of leaders in an organization. They aren’t necessarily large-scale investments, nor do they require head-count reductions. Almost every new leader’s first move is to reorganize the company/division/team/etc. They come in and say, “The old system didn’t work, so we will do this instead.” But, of course, because there is no perfect system, the new system creates new problems while solving others. When this happens, many leaders fall down the transformation effort rabbit hole and start trying new management techniques, hoping to find one that will solve all their problems. For example, a global consumer goods manufacturer wanted to increase collaboration between its regional offices and its core functions. The company was organized around the core functions, so managers thought that they could solve the problem by creating a mix of the functions and the regional centers. That, however, didn’t work because suddenly it was no longer clear who had decision-making power in terms of new-product development and strategy. It also became less clear who would get credit. If sales improved in India, would that be because the sales teams had figured something out or because the leaders in the Indian offices figured something out? This uncertainty led to a high amount of waste, internal jockeying for credit, and distrust. All of this slowed the innovation pipeline and created more fear. Leadership then decided that the answer to their problems would be a transformation to improve innovation, so they brought in an Agile expert. Leadership kept cycling through new organizational systems, ignoring the factor that caused each transformation effort to fail—fear. Worse, in creating constant uncertainty, they drove up the fear quotient even further.

SUBOPTIMAL CONVERSATIONS ON DIVERSITY, EQUITY, AND INCLUSION. Greater diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) are not just moral imperatives, they also carry significant utilitarian benefits. A study by McKinsey & Company and the Society for Human Research Management (SHRM) evaluated the performance of organizations with different levels of workplace diversity. The study found that organizations that exhibit gender and ethnic diversity are, respectively, 15 and 35 percent more likely to outperform less diverse organizations.6 And yet many organizations struggle with this issue. In private conversations with us, senior leaders from several organizations across industries acknowledged that employees often view discussions of DEI as a minefield. We’ve heard that people of color are weary of these conversations because far too often they only result in someone saying something that opens an old wound, whereas workers from more privileged backgrounds are afraid to engage because they don’t want to make a mistake and say the wrong thing. As a result, people either never have these conversations or only engage in them superficially. A standard vocabulary around diversity and inclusion has spread throughout many large corporations, and it is far too easy for people to parrot these buzzwords without making any real changes to how they see the world and behave within it.

It’s important to understand that having these conversations in a way that can create real change requires a tremendous amount of vulnerability—on all sides. It takes great skill in managing your own fear to have open conversations on difficult topics, to listen deeply to others, to empathize, and to understand the underlying fears and humanity we all share.

LACKLUSTER EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT. As a valuation expert and collaborative consultant, David Bookbinder writes in The New ROI: Return on Individuals, “The value of a business is a function of how well the financial capital and the intellectual capital are managed by the human capital. You’d better get the human capital part right.”7 To get the most out of the human capital, you need employees to be engaged enough to put in discretionary effort: to go above and beyond their job descriptions, to find ways to improve their processes, and to bring all their creativity to work with them. When there is a great deal of fear in an organization, especially interpersonal fear, employees put in far less discretionary effort. Rather than leaning into difficult situations, employees lean back and wait for someone else to make decisions and act.

Unfear is not about eliminating fear. Even if this were possible, it would be counterproductive. The goal is to shift the story we carry within us about fear and to see the opportunity for learning and growth that fear offers us as an individual, a team, and an organization. Accomplishing this shift results in a dramatically different organization—an unfear organization.

Excerpt from Unfear: Transform Your Organization to Create Breakthrough Performance and Employee Well-Being

by Gaurav Bhatnagar and Mark Minukas, pp. 15-21 (McGraw Hill, November 2021).

Copyright © 2022 by Co-Creation Partners, Inc., Gaurav Bhatnagar, and Mark Minukas.

Reprinted with permission of McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Gaurav Bhatnagar is the founder of Co-Creation Partners and has dedicated more than two decades to helping companies thrive and achieve breakthrough performance. Since founding Co-Creation Partners in 2010, he has designed and led programs and workshops for private, public, and social-sector clients across multiple industries, including financial services, basic materials, manufacturing, healthcare, and technology.

Mark Minukas is the managing partner of Co-Creation Partners and works with clients across multiple industries, including financial services, high tech, biotech manufacturing, IT services, and governmental offices, to deliver both top- and bottom-line improvements and build high-performing operations. An engineer by training, he was a Navy officer and member of the US Naval Construction Battalion (Seabees) and the Navy Dive Community.

Endnotes

1. International Data Corporation, “Worldwide Spending on Digital Transformation Will Reach $2.3 Trillion in 2023, More Than Half of All ICT Spending, According to a New IDC Spending Guide,” IDC Worldwide Semiannual Digital Transformation Spending Guide, October 28, 2019.

2. Patrick Forth, Tom Reichert, Romain de Laubier, and Saibal Chakraborty, “Flipping the Odds of Digital Transformation Success,” Boston Consulting Group, October 29, 2020.

3. Patrick Forth, Tom Reichert, Romain de Laubier, and Saibal Chakraborty, “Flipping the Odds of Digital Transformation Success,” Boston Consulting Group, October 29, 2020, p. 7.

4. Patrick Forth, Tom Reichert, Romain de Laubier, and Saibal Chakraborty, “Flipping the Odds of Digital Transformation Success,” Boston Consulting Group, October 29, 2020, p. 1.

5. Richard Barrett, Liberating the Corporate Soul: Building a Visionary Organization (Routledge, November 24, 2015).

6. Sundiatu Dixon-Fyle, Kevin Dolan, Vivian Hunt, and Sara Prince, “Diversity Wins: How Inclusion Matters,” McKinsey & Company, May 19, 2020.

7. Dave Bookbinder, The NEW ROI: Return on Individuals: Do You Believe That People Are Your Company’s Most Valuable Asset? (Limelight Publishing, September 18, 2017).