Price Wars: How the Commodities Markets Made Our Chaotic World

February 11, 2022

In his new book (and documentary of the same name), Rupert Russell explains how moves in the commodities markets have created a pattern of rising prices of instability that have brought chaos and destruction to people and communities across the globe.

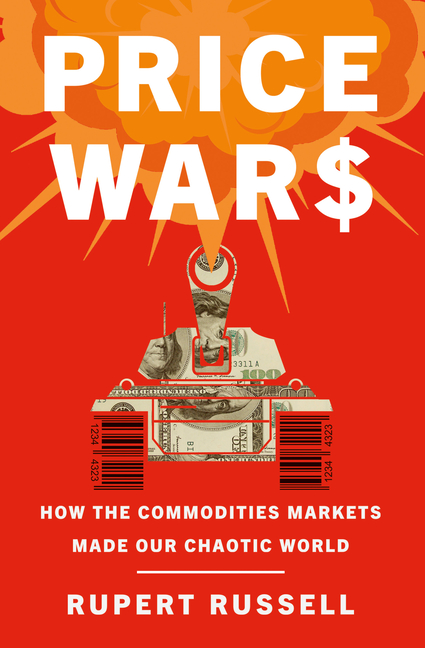

Price Wars: How the Commodities Markets Made Our Chaotic World by Rupert Russell, Doubleday

Price Wars: How the Commodities Markets Made Our Chaotic World by Rupert Russell, Doubleday

Do you want to know why food or oil prices might spike even in years when production has reached historic highs? Rupert Russell suggests, at various points throughout his new book, some thought experiments. “Imagine an island world filled with just Jeff Goldblums and T-Rexes.” Or consider the relationship between actor Anne Hathaway’s success and the stock price of Warren Buffet’s company, Berkshire Hathaway. Which is to say, markets make little sense sometimes, but you can often decipher what is going on when you stop assuming they act rationally. Unfortunately, it is not a game. Irrationality in markets can translate into chaos and instability in the real world; it has very real implications and consequences. We witnessed this clearly during the Great Recession, when banks gorged themselves on bundles of predatory mortgage loans with little tether to reality and brought the world to the brink of economic collapse, ultimately pushing many individuals, families, and small businesses over that brink while rescuing themselves with our tax dollars.

Since then, it seems like chaos in the world has only accelerated, and it might once again have something to do with a fundamental irrationality in the market—this time in commodity markets. As Russell writes:

Between 2005 and 2008, global food prices had risen by 83 percent as the price of wheat more than doubled. As the prices surged, over 150 million people were pushed into poverty and 80 million into hunger in 2008 alone. Riots broke out in forty-eight countries from India to Egypt to Argentina. Even Italy was rocked by “pasta protests.”

This occurred even though food production was at historic highs. I am always hesitant to attribute the challenges we face to a single, simple culprit, as so many talking heads do. Different sides find different culprits, faulting social media, the liberal media, Fox News or right-wing talk radio, the Democrats or Republicans, capitalism run amok or the slow creep of socialism, high taxes or the wealthy not paying their fair share of them, racism or critical race theory, the Boomers or Millennials, religious fundamentalism or us straying from it, the breakdown of the family unit or economic policies that make it so hard for working families to make ends meet.

But food, like housing, is such a fundamental human need, and the consequences so dire when it is not on the table, that it can and has caused literal revolutions throughout history. The history of the French Revolution, as we know well through the story of Marie Antoinette, began with bread. Like the French Revolution, there were many long-standing grievances against governments in the Middle East, but many of the protests that ignited the Arab Spring were against rising food prices. But as Russell explains, there was one significant difference:

The high bread prices that triggered the French Revolution were the result of a poor harvest. There was less grain, so prices rose. However, during the Arab Spring, and the Global Food Crisis before it, there was plenty of food. In fact, both years had seen the most food produced in history. So why did prices soar at a time of abundance? What was the trigger behind the trigger?

Well, it may have been due to a complex derivative product called a “commodity index fund” that index speculators were buying up at record numbers. As Russell reports, “commodity index funds had grown from $13 billion in 2003 to $260 billion in the middle of March 2006.” As the financial crisis hit, and the mortgage market blew up, putting more money into commodities was seen as a safe bet, and even though production was up and demand was down due to the recession, the rush of investors and speculation in commodities caused prices to rise.

And it wasn’t just food and oil: the prices of all commodities were moving upwards together for the first time. There was no reason why the supply of American wheat, Indian cotton, Guatemalan coffee, Russian oil, Chilean nickel or Qatari natural gas should be connected. It was unprecedented.

The chaos this created is not just theoretical or confined to markets, but very real and long-lasting, a reality Russell confronted repeatedly in his extensive travels to write this book and make his documentary of the same title. One of the physical manifestations of it is in the estimated one million tons of rubble in the Old City of Mosul that may take ten to twenty years to clear. He surveys the scene from a Catholic Church that had been used by ISIS as a prison.

From this vantage point atop the Old City I can see the Tigris draw a line between order and disorder. Like the River Acheron in Dante’s Inferno, which marked the boundary of Hell, the Tigris carves out an island of ruins from an otherwise contented landscape. Over the water I see three broken bridges that connect the two worlds. Their mid-sections have imploded; one is just an empty space, another has fallen down, leading the road into the riverbed. Yet this medieval metaphor is deceptive. Mosul is not cut off from the modern world but intimately bound to it. The devastation was created through a butterfly effect that started with magical derivatives traded thousands of miles away. The “financial weapons of mass destruction”—as Warren Buffett called them—had become actual artillery fire, mortars, missiles and grenades. The ruins around me were quite literally, as Joseph Stiglitz told me, the “collateral damage” of the financial sector’s pursuit of a few percentage points to add to their balance sheets. And the damage was ongoing.

The connections he is making may seem tenuous at first, but as he walks you through the way the food-price spikes led to the Arab Spring, which led to civil war breaking out across the Middle East, which caused oil prices to spike, you begin to see how chaos in markets bred chaos in the real world, which was then incorporated as information that caused commodity prices and markets to spike even further.

As he shares what he has witnessed on the ground in the real world, he also explains the history of ideas ranging from the butterfly effect to chaos theory, ties in Robert Shiller’s concept of narrative economics (and, lest you think anyone is suggesting that finance is all bad, might I point you to Shiller’s Finance and the Good Society?) and how trend-following amplifies price moves and fuels bubbles, and so much more. I’ve touched briefly on his journeys in the Middle East, but he travels the entire globe following the threads of commodities markets and their influence on the physical world.

We all know the power of stories, and how influential they are in our personal lives. What Russell explains through all this is how powerful they are in markets, how they act as contagions, how they can both narrate and deceive. Prices “are driven not by scientific rationality,” he suggests. “but emotional contagion.” Money is, after all, a social construct, and acquiring wealth is a social game. But the derivative-driven markets of today operate on a kind of magical thinking, one that is “not a ‘madness’ or a ‘delusion’ but a business model” based on manipulation. In a deregulated environment, trading in ever more complex forms of derivatives, a place like the Chicago Mercantile Exchange becomes more opaque and can be used to obscure as much information (and risk) as it is supposed to reveal (and manage).

[N]ew derivatives were different from the futures contracts for wheat and oil sold at the exchanges. Those contracts were regulated, they were simple and standardized, and traded by thousands of people. Farmers and speculators alike understood them, and understood what would happen if a farmer couldn’t deliver her quota or the grain delivered wasn’t the correct quality. In contrast, this new derivative market was neither regulated, public nor standardized. They were called “over-the-counter" derivatives and sold privately between financial entities. They were bespoke, hundreds of pages long and impenetrable to even seasoned financial professionals.

But even those who practice that magic can’t always explain what is behind it, or predict what the ultimate reveal of the trick will be. Even Alan Greenspan, who testified before Congress that deregulating derivatives would make the market safer, later admitted that he had “found a flaw” in his thinking—but only after he “had let these magical prices rule, and their reign has plunged the world in to chaos.”

I began this review with a little levity, but there is not a whole lot of it in the book. It is deadly serious, for the most part, because the results have been seriously deadly. In explaining the absurdity that currently exists in markets, how “the rule of prices is chaotic” and has been throughout history, we also witness the lives of those affected by that absurdity, the chaos it has wrought, and the very real monsters it has unleashed on the world today.