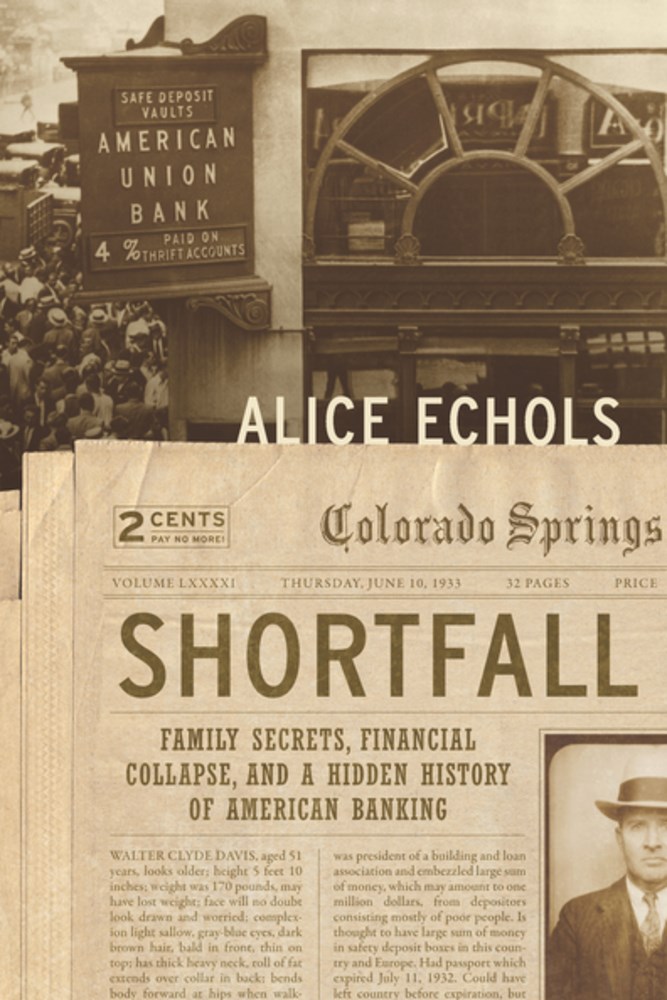

Shortfall: Family Secrets, Financial Collapse, and a Hidden History of American Banking

October 27, 2017

Alice Echols tells the story of her grandfather, It's a Wonderful Life, and a lie at the heart of the American narrative.

Shortfall: Family Secrets, Financial Collapse, and a Hidden History of American Banking by Alice Echols, The New Press, 320 pages, Hardcover, October 2016, ISBN 9781620973035

George Bailey, the reluctant manager of a building and loan association in the fictional town of Bedford Falls, New York, is one of great heroes of American cinema. It is perhaps Jimmy Stewart’s best-known roles. But Frank Capra's 1946 film, It's a Wonderful Life, was a flop when it was first released, and lost over a half million dollars at the box office. Perhaps that was because it didn’t resonate with the reality so many moviegoers would have experienced in the previous decade, when the building and loan industry collapsed during the great depression, wiping out many Americans’ hard-earned savings and expelling them from their homes. It is a story that in too many ways mirrors the recent subprime mortgage crisis, and a story that has largely remained untold. Historian Alice Echols remedies that in her new book, Shortfall: Family Secrets, Financial Collapse, and a Hidden History of American Banking.

Building and loan associations (B&Ls) were originally an English transplant, where they began as “self-help societies organized by the working classes—people not served by the country’s national banks.” They were usually organized locally and run as cooperatives, with no official offices or paid officers. The were founded for the benefit of their members, not to profit from them, and most operated with modest means—sixty percent of them had fewer than 200 members. Yet, they were so popular that:

By 1893 there were 5,838 B&Ls operating in every state and territory, with 1.4 million members. There assets came to $473 million, and they held mortgages of half a billion dollars. After private lenders and savings banks, building and loans were the third-biggest home mortgage lenders.

Of course, where there is that much money, there are those that are going to come in to try and get a piece of it, and in that same year of 1893, there were already 240 for-profit companies that called themselves building and loans, with 400,000 members. Over time, they would become the predominant type of B&L, and these private interests would form the B&L league, which “would become one of the country’s strongest and most influential trade groups.” It had laws written in the for-profits favor, while largely avoiding regulation by playing up the original collective, philanthropic image and nature of B&Ls, even as they abandoned it.

Alice Echols’s grandfather, Walter Davis, was the proprietor of one such building and loan scheme. Before buying the City Savings Building and Loan Association from three Colorado Springs businessman in 1914, he was what would best be described as a small time loan shark. To tell the story of Walter Davis, it is necessary to tell the story of Colorado Springs, which provides a great microcosm of the American dream at the time:

During the years that Cripple Creek produced more gold than anywhere else in the country Colorado Springs was the American dream on steroids. America might boast of streets paved with gold, but the downtown streets of Colorado Springs were actually paved with gold. In 1920 fifteen hundred carloads of crushed low-grade gold ore from the Vindicator Mine in Cripple Creek were added to the city’s paving mixture, making the town’s streets gleam.

There were four men operating building and loan associations in Colorado Springs at this time, all of them operating, basically, as pyramid schemes. Like the nearby gold mines, they were largely an extraction industry, except that in their case, they were simply embezzling their working class clients’ hard-earned cash. In It's a Wonderful Life, a crisis begins when George Bailey’s absentminded Uncle Billy loses an $8,000 deposit on the way to the bank on Christmas Eve. In real life, the operator of the Hollywood Building and Loan Association, Gilbert H. Beesemeyer, admitted the week of Christmas, 1930, that there was “a lot more wrong with the books that you can imagine,” and told a crowded courtroom that he was “a dirty crook.” His books contained an $8 million shortfall. In real life Colorado Springs, building and loan operator Willis Sims took his own life three days after Christmas, 1931.

As for the depositors in the [building and loan he operated], a little more than a year after Sims’s suicide they learned that the shortfall there totaled nearly $180,000 and that they would receive only 20 percent of the money they had on deposit there. As late as September 1936 depositors had yet to receive a penny.

The suicide set in motion a series of events that eventually exposed the other building and loans in town, and Walter Davis himself. The shortfall at Walter Davis’s City Building and Loan, the largest B&L in Colorado Springs, was $1.25 million. By the time it was discovered, however, not only was the money missing, Walter Davis himself was nowhere to be found. He went on the lam, and became one of the most wanted men in America, a case that played out in the national media. Some of the 3,600 working class depositors he had swindled even hatched a plan to kidnap the Davis’s daughter, the author’s mother Dorothy, in an attempt to force his return.

Shortfall is “a narrative in which both an individual family and the American economy are moving inexorably toward ruin.” Both Echols’s family and the economy would eventually recover, but many of those affected would not, and the story would be forgotten. Echols herself didn’t know the story of her grandfather until her family house was being sold shortly before her mother passed, and boxes of papers and personal correspondence were found in the attic. What she discovered on the journey to discover more and write this story is a hidden history of the building and loan scandal that has affected “the relationship between capitalism, class, and conservatism in America” to this day. She also uncovered how it has personally affected her life, how the wealth her grandfather embezzled from depositors eventually helped give her a leg up in life. It is a history, she writes, “of America’s uneven playing field, or one significant corner of it.”

Shortfall is a family history, a history of Colorado Springs and the American West’s complicated relationship with the Federal Government, and a history of “thrift industries”—the building and loan associations, and the savings and loan associations that followed, and collapsed in scandal, behind them—in the United States. It is a story of how we forget, and prefer Hollywood fantasy of redemption over a reality that remains with us, even after a similar collapse in the subprime mortgage industry. As Echols writes:

Several years ago the chairman of one of the country’s largest check-cashing companies argued that critics who attack such businesses for turning a profit in low-income communities had it all wrong. “We’re the George Baileys here,” he insisted.

Which may be true, but the real life George Baileys of the world were mostly dirty crooks, and their crimes have reverberated through the generations, shaping American capitalism and class to this day.