-

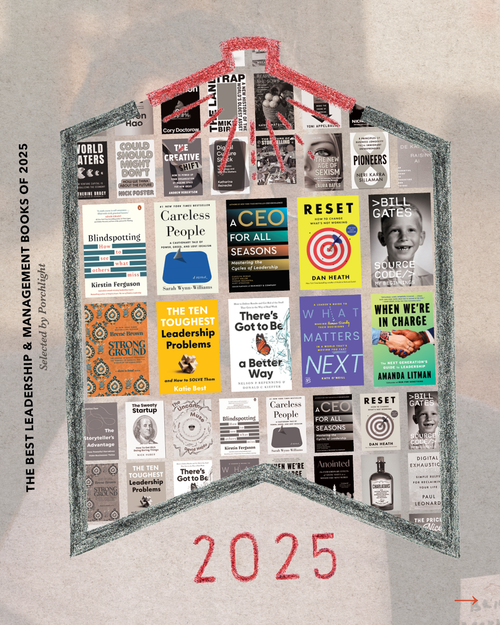

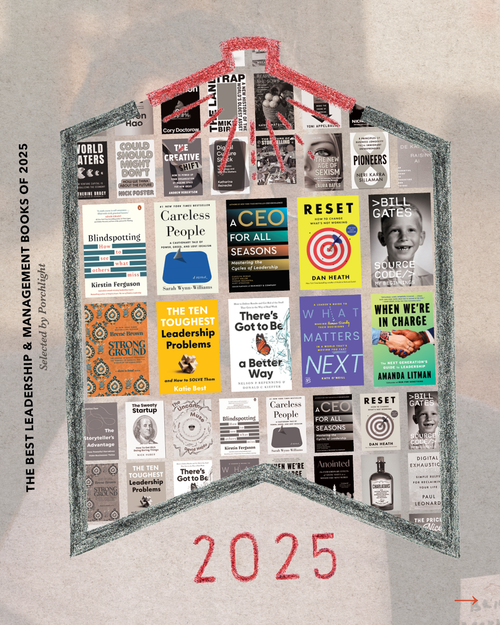

Book Excerpts from the Leadership & Management Category

In an increasingly uncertain world, the job of leaders and managers is becoming even more difficult. These ten books offer guidance on the way through.

-

An Excerpt from There's Got to Be a Better Way: How to Deliver Results and Get Rid of the Stuff That Gets in the Way of Real Work

An excerpt from There's Got to Be a Better Way by Nelson P. Repenning & Donald C. Kieffer, published by Basic Venture and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Leadership & Management category.

-

An Excerpt from When We're in Charge: The Next Generation's Guide to Leadership

An excerpt from When We're in Charge by Amanda Litman, published by Crooked Media Reads and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Leadership & Management category.

-

An Excerpt from What Matters Next: A Leader's Guide to Making Human-Friendly Tech Decisions in a World That's Moving Too Fast

An excerpt from What Matters Next by Kate O'Neill, published by Wiley and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Leadership & Management category.

-

An Excerpt from Reset: How to Change What's Not Working

An excerpt from Reset by Dan Heath, published by Avid Reader Press and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Leadership & Management category.

-

An Excerpt from Blindspotting: How to See What Others Miss

An excerpt from Blindspotting by Kirstin Ferguson, longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Leadership & Management category.

-

Book Excerpts from the Innovation & Creativity Category

From entrepreneurship to AI, idea-generation to the power of storytelling, these 10 books all help us consider our place in the ongoing project of humanity's progress and how our work might contribute to it.

-

An Excerpt from The Uncanny Muse: Music, Art, and Machines from Automata to AI

An excerpt from The Uncanny Muse by David Hajdu, published by W. W. Norton & Company and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Innovation & Creativity category.

-

An Excerpt from The Sweaty Startup: How to Get Rich Doing Boring Things

An excerpt from The Sweaty Startup by Nick Huber, published by Harper Business and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Innovation & Creativity category.

-

An Excerpt from The Storyteller's Advantage: How Powerful Narratives Make Businesses Thrive

An excerpt from The Storyteller's Advantage by Christina Farr, published by Basic Venture and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Innovation & Creativity category.

-

An Excerpt from Pioneers: 8 Principles of Business Longevity from Immigrant Entrepreneurs

An excerpt from Pioneers by Neri Karra Sillaman, published by Wiley and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Innovation & Creativity category.

-

An Excerpt from The New Age of Sexism: How AI and Emerging Technologies Are Reinventing Misogyny

An excerpt from The New Age of Sexism by Laura Bates, published by Sourcebooks and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Innovation & Creativity category.

-

An Excerpt from The Future of Storytelling: How Immersive Experiences Are Transforming Our World

An excerpt from The Future of Storytelling by Charles Melcher, published by Artisan Books and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Innovation & Creativity category

-

An Excerpt from The Creative Shift: How to Power Up Your Organization by Making Space for New Ideas

An excerpt from The Creative Shift by Andrew Robertson, published by Basic Venture and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Innovation & Creativity category.

-

An Excerpt from Could Should Might Don't: How We Think about the Future

An excerpt from Could Should Might Don't by Nick Foster, published by MCD and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Innovation & Creativity category.

-

Book Excerpts from the Personal Development & Human Behavior Category

At a time when business books and self-help are increasingly indistinguishable from one another, how do we consider which books to include in our Personal Development & Human Behavior category?

-

An Excerpt from The Price of Nice: Why Comfort Keeps Us Stuck and 4 Actions for Real Change

An excerpt from The Price of Nice by Amira Barger, published by Berrett-Koehler and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Personal Development & Human Behavior category.

-

An Excerpt from Play the Game. Change the Game. Leave the Game.: Pathways to Black Empowerment, Prosperity, and Joy

An excerpt from Play the Game. Change the Game. Leave the Game. by Robert Livingston, published by Crown Currency and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Personal Development & Human Behavior category.

-

An Excerpt from The Ideological Brain: The Radical Science of Flexible Thinking

An excerpt from The Ideological Brain by Leor Zmigrod, published by Henry Holt & Company and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Personal Development & Human Behavior category.

-

An Excerpt from How to Be Free: A Proven Guide to Escaping Life's Hidden Prisons

An excerpt from How to Be Free by Shaka Senghor, published by Authors Equity and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Personal Development & Human Behavior category.

-

An Excerpt from Don't Be Yourself: Why Authenticity Is Overrated (and What to Do Instead)

An excerpt from Don't Be Yourself by Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, published by Harvard Business Review Press and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Personal Development & Human Behavior category.

-

An Excerpt from Digital Exhaustion: Simple Rules for Reclaiming Your Life

An excerpt from Digital Exhaustion by Paul Leonardi, published by Riverhead Books and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Personal Development & Human Behavior category.

-

An Excerpt from Charlatans: How Grifters, Swindlers, and Hucksters Bamboozle the Media, the Markets, and the Masses

An excerpt from Charlatans by Moises Naim and Quico Toro, published by Basic Books and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Personal Development & Human Behavior category.

-

An Excerpt from Anointed: The Extraordinary Effects of Social Status in a Winner-Take-Most World

An excerpt from Anointed by Toby Stuart, published by Simon & Schuster and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Personal Development & Human Behavior category.

-

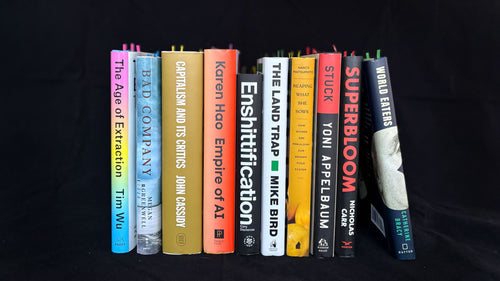

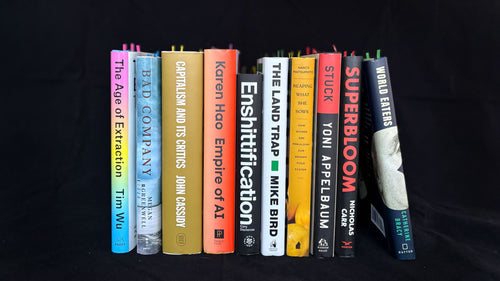

Book Excerpts from the Current Events & Public Affairs Category

At first glance, the 10 books in our Current Events & Public Affairs category appear to be focused almost entirely on the negative. We believe that, once you spend some time between their covers, you will find they point the way to positive change and a more just and prosperous future for all.

-

An Excerpt from World Eaters: How Venture Capital Is Cannibalizing the Economy

An excerpt from World Eaters by Catherine Bracy, published by Dutton and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Current Events & Public Affairs category.

-

An Excerpt from Searches: Selfhood in the Digital Age

An excerpt from Searches by Vauhini Vara, published by Pantheon and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Personal Development & Human Behavior category.

-

An Excerpt from Superbloom: How Technologies of Connection Tear Us Apart

An excerpt from Superbloom by Nicholas Carr, published by W. W. Norton & Company and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Current Events & Public Affairs category.

-

An Excerpt from Stuck: How the Privileged and the Propertied Broke the Engine of American Opportunity

An excerpt from Stuck by Yoni Applebaum published by Random House and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Current Events & Public Affairs category.

-

An Excerpt from Reaping What She Sows: How Women Are Rebuilding Our Broken Food System

An excerpt from Reaping What She Sows by Nancy Matsumoto, published by Melville House and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Current Events & Public Affairs category

-

An Excerpt from The Land Trap: A New History of the World's Oldest Asset

An excerpt from The Land Trap by Mike Bird, published by Portfolio and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Current Events & Public Affairs category.

-

An Excerpt from Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do about It

An excerpt from Enshittification by Cory Doctorow, published by MCD and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Current Events & Public Affairs category.

-

An Excerpt from Empire of AI: Dreams and Nightmares in Sam Altman's OpenAI

An excerpt from Empire of AI by Karen Hao, published by Penguin Press and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Current Events & Public Affairs category.

-

An Excerpt from Capitalism and Its Critics: A History: From the Industrial Revolution to AI

An excerpt from Capitalism and Its Critics by John Cassidy, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Current Events & Public Affairs category

-

An Excerpt from Bad Company: Private Equity and the Death of the American Dream

An excerpt from Bad Company by Megan Greenwell, published by Dey Street Books and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Current Events & Public Affairs category.

-

An Excerpt from The Age of Extraction: How Tech Platforms Conquered the Economy and Threaten Our Future Prosperity

An excerpt from The Age of Extraction by Tim Wu, published by Knopf and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Current Events & Public Affairs category.

-

Tech Agnostic | An Excerpt from the 2024 Porchlight Big Ideas & New Perspectives Book of the Year

The 2024 Big Ideas & New Perspectives Book of the Year is Tech Agnostic: How Technology Became the World's Most Powerful Religion, and Why It Desperately Needs a Reformation by Greg Epstein, published by MIT Press.

-

The Vagina Business | An Excerpt from the 2024 Porchlight Creativity & Innovation Book of the Year

The 2024 Creativity and Innovation Book of the Year is The Vagina Business: The Innovative Breakthroughs That Could Change Everything in Women's Health by Marina Gerner, published by Sourcebooks.

-

Higher Ground | An Excerpt from the 2024 Porchlight Leadership and Strategy Book of the Year

The 2024 Leadership and Strategy Book of the Year is Higher Ground: How Business Can Do the Right Thing in a Turbulent World by Alison Taylor, published by Harvard Business Review Press.

-

The Truth About Immigration | An Excerpt from the 2024 Porchlight Current Events & Public Affairs Book of the Year

The 2024 Current Events & Public Affairs Book of the Year is The Truth about Immigration: Why Successful Societies Welcome Newcomers by Zeke Hernandez, published by St. Martin's Press.

-

The Problem with Change | An Excerpt from the 2024 Porchlight Management & Workplace Culture Book of the Year

The 2024 Porchlight Management & Workplace Culture Book of the Year is The Problem with Change: And the Essential Nature of Human Performance by Ashley Goodall, published by Little, Brown Spark.

-

Say It Well | An Excerpt from 2024 Porchlight Marketing & Communications/Sales & Influence Book of the Year

The Marketing & Communications/Sales & Influence Book of the Year is Say It Well: Find Your Voice, Speak Your Mind, Inspire Any Audience by Terry Szuplat, published by Harper Business.

-

Unlearning Silence | An Excerpt from the 2024 Porchlight Personal Development & Human Behavior Book of the Year

The 2024 Personal Development & Human Behavior Book of the Year is Unlearning Silence: How to Speak Your Mind, Unleash Talent, and Live More Fully by Elaine Lin Hering, published by Penguin Life.

-

Savings and Trust | An Excerpt from the 2024 Porchlight Narrative & Biography Book of the Year

The 2024 Narrative & Biography Book of the Year is Savings and Trust: The Rise and Betrayal of the Freedman's Bank by Justene Hill Edwards, published by W. W. Norton & Company.

-

An Excerpt from Fair Doses by Seth Berkley

How vaccines became the world's most powerful and widely distributed health intervention, and the inside story of the challenging race to deliver COVID-19 vaccines globally.

-

An Excerpt from Lucky By Design

Wharton economist and market designer Judd Kessler pulls back the curtain on hidden markets that determine who gets what in everyday life—and how to tip the scales in your favor.

-

An Excerpt from 100 Best Books for Work and Life

100 Best Books for Work and Life will help you cut through the clutter and discover the books that are worth your time and will enrich your life.

-

An Excerpt from Mission Driven: The Path to a Life of Purpose

Former Navy SEAL commander, White House Fellow, and nonprofit and business leader Mike Hayes offers an inspiring playbook for understanding and achieving your most rewarding and purposeful life.

-

An Excerpt from Dragon on Centre Street

In this excerpt from Dragon on Centre Street, New York Times reporter Jonah E. Bromwich recounts how he and his team covered the unfolding story of the unprecedented indictment of a former U.S. president.

-

An Excerpt from The Power of Mattering

People thrive when they are seen, heard, and valued. Leadership development facilitator Zach Mercurio offers a simple framework for making workplace interactions more meaningful and affirmative.

-

An Excerpt from Rethinking Medications

Many medications taken by Americans are either excessively expensive or carry significant risks. Dr. Jerry Avorn shares his insights on how we got here and proposes practical solutions to improve the system.

-

An Excerpt from Unstoppable Entrepreneurs

Lori Rosenkopf, Vice Dean of Entrepreneurship at the Wharton School, offers a guidebook encouraging readers to tap into their entrepreneurial potential.

-

An Excerpt from Validation

Clinical psychologist Caroline Fleck highlights validation—the acceptance of others' views and values—as a key to influencing others and fostering harmony in the workplace.

-

An Excerpt from Meaningful Work

Wes Adams and Tamara Myles write that strong employee engagement, happiness, and productivity stem from leaders helping employees find meaning in their work.

-

An Excerpt from Wild Courage

Google executive Jenny Wood writes about nine unconventional personal traits that, when effectively utilized, can lead to life-changing success.

-

An Excerpt from You're the Boss

Executive coach Sabina Nawaz offers a guide on gracefully managing the pressures of power, helping readers become the leaders they aspire to be and whom others are excited to work with.

-

An Excerpt from Managing Up

To cultivate a lasting professional relationship, focus on how you can help the other person, writes executive coach Melody Wilding.

-

An Excerpt from Thriving Together

Expert community builder and former Buddhist monk David Viafora writes that the simple act of showing appreciation for one another has the power to nurture thriving communities.

-

An Excerpt from Now It All Makes Sense

Alex Partridge, mental health advocate and host of the podcast ADHD Chatter, shares his life story and strategies for living and thriving with ADHD.

-

An Excerpt from Predatory Data

To shape the future of tech, we must look to the past and draw from the traditions of the researchers, artists, and activists who have envisioned futures that defy probability, writes scholar Anita Say Chan.

-

An Excerpt from Nonlinear

Kevin Bethune highlights the necessity of incorporating a broader range of perspectives in the design process, resulting in innovative solutions that more accurately reflect and address our diverse society.

-

An Excerpt from Make Work Fair

Believing in equal opportunity is essential—but it isn’t enough. Offering an evidence-based blueprint, Make Work Fair shows you how to make it a reality, no matter your role, seniority, responsibilities, or where you are in the world.

-

An Excerpt from Talk

Even the simplest conversations can be tricky, but when done well, they can become sources of immense joy that make us feel cherished and alive, writes Dr. Alison Wood Brooks.

-

An Excerpt from The Seven Tensions of Negotiation

Sitting down to negotiate is like getting ready to throw or defend against a punch — we feel the tension. When we teach ourselves to feel, assess, neutralize, and respond to tension, we can successfully maneuver any negotiation.

-

An Excerpt from Mindmasters

Algorithms influence our psychological experiences, often without our awareness. However, Sandra Matz argues that we can unite to leverage big data for our benefit. benefit.

-

An Excerpt from F*ck Happiness

Artist and therapist Shawn Léon Nowotnik encourages readers to think beyond pursuing happiness and embrace all of life's complexities.

-

An Excerpt from Extraordinary Learning for All

The leadership team at Transcend Education highlights insights from innovators in education and presents a framework for creating a more meaningful schooling experience for all students.

-

An Excerpt from Main Street Millionaire

Codie Sanchez encourages readers to pursue entrepreneurship by taking a look at the established local businesses whose founders need successors to continue their legacies.

-

An Excerpt from Unblock Your Purpose

Francesca Sipma, the founder of HypnoBreathwork®, offers a detailed guide to overcoming mental blocks, finding a flow state, and uncovering one's deeper life purpose.

-

An Excerpt from Work-Life Tango

Corporate wellness advocate Kristel Bauer writes that achieving a work-life balance is not just about surviving—it's about thriving and finding the courage to embrace a fulfilling life.

-

An Excerpt from Crisis Capable

Fabiana Lacerca-Allen uses her expertise in high-stakes negotiations to help readers navigate moral dilemmas and identify when to leave situations that conflict with their values.

-

An Excerpt from Your Stone Age Brain in the Screen Age

Neurologist Richard Cytowic explores the connection between our Stone Age-wired brains and contemporary screen addictions, offering insights on how to regain calm and focus.

-

An Excerpt from The Split

Shaun Rein writes that the Chinese consumer market has significant untapped potential, and recent economic policy changes offer investors an ideal opportunity to engage.

-

An Excerpt from Ultimate Profit Management

Use this book as a guide. In it, the author covers the most important aspects of reasonable, prudent growth that will avoid debt and allow you, your partners, and business associates a productive and non-stressful existence with a business that grows and profits correctly.

-

An Excerpt from The Five Talents That Really Matter

A former Gallup Global Leadership Research and Development leader demystifies the aura and complexity surrounding high performing leaders through original research and interviews with high-performing global leaders.

-

An Excerpt from Shy by Design

Michael Thompson provides a powerful guide to leading with quiet conviction and uplifting others on the journey to success.

-

An Excerpt from Taming Silicon Valley

Leading AI expert Gary Marcus simplifies the concept of artificial intelligence, highlights its potential and dangers, and emphasizes the need for accountability from policymakers and tech companies.

-

An Excerpt from The Unlocked Leader

A practical and impactful guide to identify and free yourself from the mind-traps that hold you back so that you can become a powerful human leader and unlock extraordinary performance.

-

An Excerpt from Likable Badass

Behavioral scientist Alison Fragale offers powerful new insights and a practical playbook for women to advance in any workplace, full of tips, tricks, and strategies to help secure that elusive corner office.

-

An Excerpt from Give to Grow

"It's always your move and there's always a way to be helpful."

-

An Excerpt from Thinking Bigger

A guide for women entrepreneurs to help them get the financing they need to build big businesses and change our world.

-

An Excerpt from The Tree Collectors

Fifty gorgeously illustrated vignettes of remarkable people whose lives have been transformed by their obsessive passion for trees--from Amy Stewart, the New York Times bestselling author of The Drunken Botanist.

-

An Excerpt from The Mind's Mirror

An exciting introduction to the true potential of AI from the director of MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory.

-

An Excerpt from The 8 Laws of Customer-Focused Leadership

A leadership playbook for making customer experience a core aspect of your business.

-

An Excerpt from The Power of Instinct

Award-winning Fortune 500 brand consultant and behavioral expert Leslie Zane shatters conventional marketing wisdom, showing readers how to tap into the hidden brain where instinct prevails, creating a powerful network of connections that drive people to buy your product, company, or vision.

-

An Excerpt from Shocks, Crises, and False Alarms

An essential new guide to navigating macroeconomic risk.

-

An Excerpt from Smart, Not Loud

Business communication expert Jessica Chen provides a complete guide to help individuals effectively advocate for themselves while maintaining authenticity in the workplace.

-

An Excerpt from Unjust Debts

A groundbreaking look at the hidden role of bankruptcy in perpetuating inequality in America, from an expert in the field.

-

An Excerpt from Assembling Tomorrow

A powerful guide to why even the most well-intentioned innovations go haywire, and the surprising ways we can change course to create a more positive future, by two celebrated experts working at the intersection of design, technology, and learning at Stanford University’s acclaimed d.school.

-

An Excerpt from When We Are Seen

From one of the first and few women of color to reach the c-suite in Silicon Valley, Apple’s former chief of HR, co-creator of the Apple Store culture, and first VP of inclusion and diversity, comes a heartfelt story of growing up Black and female in a world with little regard for either and a practical road map for embodying the best in yourself and emboldening others along the way.

-

An Excerpt from Stumbling Toward Inclusion

In her work with hundreds of companies and CEOs, Dr. Priya Nalkur has found that many leaders want to advance inclusion and equity in the workplace, but aren't sure how. Knowing that the stakes are high, leaders are afraid of messing up and saying the wrong thing. She has distilled her extensive coaching experience into a set of practical tools for navigating uncertain waters.