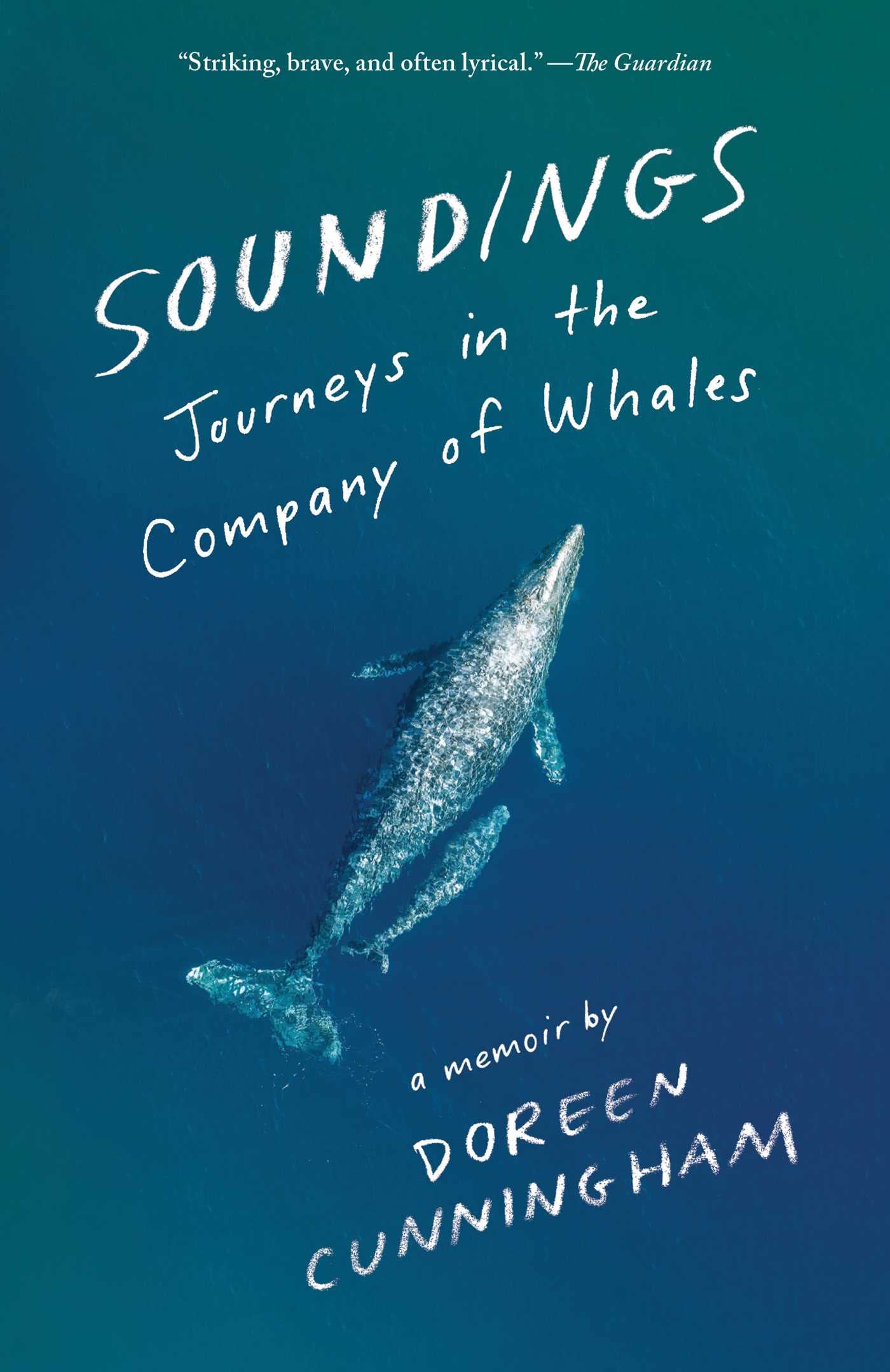

A Q&A with Doreen Cunningham

I must say I was in awe of this book. Such a captivating, raw and special offering to the world. A lovely memoir that ranges in exploration but keeps the constant tone of gratitude and discovery on this journey we call life.

Soundings is a love letter to the sea, sentient giants, those who you meet on the journey that you take in as family, and finally a love letter to herself as she finds her footing and confidence as a single parent. An extraordinary memoir, we follow Cunningham through the frigid landscapes of the Arctic following Indigenous whalers, to her journey tracking grey whales along the West coast with her two-year-old son.

As a journalist and environmentalist Doreen Cunningham worked for the BBC and eventually became a mother to small Max. After going through a difficult relationship, being a freelance writer and journalist, she found herself without a permanent residence she could reside in bouncing from hostel to hostel with her little one. In Soundings Doreen not only introduces us to the independent journalist searching the Arctic with Indigenous whalers, but to a strong resilient single mother who mimics the esteemed whale mother tending to her young. A story of strength, courage, resilience, motherhood, grief and finding yourself in the most unlikely places. The places you are meant to be.

Before this book I always had a fascination with whales. After reading this book I have a new appreciation for these grand sentient beings but also for the whalers who respect these beings while hunting them that has been a tradition in their culture for hundreds of years.

...

Porchlight Book Company: The way you intertwine your story of being a young journalist covering climate change to you journeying with your young son following the whale's migration on the West Coast with snippets of your childhood and family peppered in was wonderfully stitched together. It makes the reader nostalgic and gives such an appreciation to found family, culture, and our waters that these giant sentient beings, whales, reside in. In each page you can feel your love for these creatures, and the love you have for their existence, and the ferocity you have to see them thrive. After writing this book can you see whales surviving our mistakes, like they have survived other traumas throughout history?

Doreen Cunningham: Eeeek that’s a big question! Throughout the book I defer to scientists, people who have spent their lives studying whales and the ocean, so readers can think about that one and come to their own conclusions. It doesn’t seem as simple to me as either all the whales will die, there’s no hope, or that the whales will live happily ever after despite us. There are different things going on in the world right now, different trajectories that are gathering pace, alongside each other.

Some processes obviously have more power and money behind them than others. One strand of the book follows the birth of climate denial in oil company boardrooms when I was a child, and the way that played out with climate sceptics and false balance in the media during my journalistic career. The fossil fuel industry’s campaign to spread doubt about climate change is no longer hidden because of the work of some very fine journalists, researchers and even former employees from Exxon, who have gone on record about it. But climate denial is still playing out in politics, the media and in society at large, with terribly damaging consequences.

But my book is also about overcoming trauma, the power of kindness and the solidarity and strength we can find in building community. One example of undersea community building that I have written about involves an inspiring female gray whale nicknamed Earhart. She’s a founding member of a group of gray whales called the Sounders, who have pioneered a new food source: ghost shrimp in the waters of northern Puget Sound. John Calambokidis, who’s a leading whale expert, observed Earhart leading other whales through the intertidal zone where they feed on the shrimp. Gray whales are in trouble right now, there’s a die-off going on and a lot of whales are washing up dead, a significant proportion of them malnourished. At the same time increasing numbers of undernourished whales are joining the Sounders, interrupting their typical migration pattern to fatten up on the shrimp. Scientists think one possible reason for this change in behaviour could be a decline in the availability of prey in the grays’ main Arctic feeding grounds as it warms. That’s one hypothesis because the amphipods they like to eat need cold water.

Gray whales are thought to have survived previous climate change because they are flexible in what they eat and Earhart has helped pioneer a sort of emergency food bank there. When I’m struggling with the enormity of what we are living through, it helps me to remember her, and all the other gray whale mothers, their endurance as they travel up and down the globe with their calves, and their ability to rapidly adapt and forge new paths together through crisis.

PBC: It was quite beautiful to read as you grew and flourished during your time in the Arctic. A proclaimed vegetarian and lover of whales, you find yourself offered whale meat which, when you first arrived, made you gag. When you were about to leave, it became your favorite snack. Can you speak to how your appreciation for whales and indigenous whalers grew during your time in the Arctic? And are you still a vegetarian or have you opened that up since you explored different meats?

DC: I didn’t really know what I was getting into when I travelled to the Arctic in 2006. I’d contacted locals and explained that I wanted to listen to residents, to understand what they thought about climate change and whether it affected their everyday lives. Someone suggested that I would need to spend time with the hunters, so I wrote to the Barrow Whaling Captain’s Association and got permission to do that, but I didn’t think about what I’d eat! When I was offered whale, caribou and goose meat it just felt like basic manners to accept what I was offered in a place where food wasn’t always plentiful, where it was hard-won in a hunt that had sustained a culture for centuries. I didn’t take eating whale lightly. It had a big impact on me which I write about, but it made sense in the context of Iñupiaq culture and the hunt. There is a long history of outsiders imposing their values, culture and laws on indigenous people in the Arctic. I wasn’t interested in being part of that and that extended to what I ate while I was there. When I came back to England, I reverted to a vegetarian diet. I strongly object to intensive agricultural practices and the farming of animals for meat. I also eat vegan quite a bit, partly because one of my children wanted to try being vegan.

PBC: The Iñupiaq people of Alaska respect the land, water, and the whale when hunting. Even with the knowledge that they are so respectful of these wondrous beasts, was it hard for you to enter the hunt with the Kaleak family?

DC: I felt honoured to be staying with the Kaleak family and to have the opportunity to be immersed in Iñupiaq culture. The family’s hospitality made a big impression on me, as did being allowed to join the whaling crew. When I arrived in Utqiaġvik, I was initially very frustrated that the weather wasn’t right to go out on the ice straight away but being made to wait helped me understand what it is to be a subsistence hunter in the Arctic and gave me time to learn about the history of colonial violence against Native Alaskans. I learned that Inuit language held a different world view, where human and non-human life is spoken about in a way that implies respect and equality: there is no word for ‘it’. The spiritual dimension and sharing ethic that underpins the hunt was also carefully explained to me. Travelling out onto the ice with Kaleak crew was mind-blowing. The environment was astonishingly beautiful and hostile and as I was entirely ignorant about everything, my life depended on the crew. I listened to beluga and bowhead whales breathing and watched them pass on their ancient migration route eastwards. I was relieved that I wasn’t allowed into the umiaq when the crew paddled out after the bowheads and I didn’t see one being killed. But the hunt involves an enormous amount of effort and danger, and I was fully behind my crew.

PBC: As a journalist you have seen so many amazing and traumatic events, especially when it comes to reporting climate change. At the beginning of your career, skeptics would always be asked their opinion or the story would be cut entirely, thus creating miscommunication of the facts. Towards the end of the book, you illustrate the power of engaging in difficult conversations about climate change instead of avoiding them. By sitting down and discussing the facts, you ultimately altered the perspective of another journalist. Can you give us advice on continuing to speak about the climate, especially when it comes to the rising temperature in the waters and how it is affecting ocean life?

DC: That’s a really hard question because everyone’s perspective and voice are unique and important, I don’t want to tell people how to approach it. Pitching climate as a journalist over the years, I was often challenged by colleagues who said that climate was a boring or depressing story that would just make people switch off. But climate change was already catastrophic for some communities, those people already did not have the luxury of being able to switch off from it and that’s even more so the case today. Scientists are now able to tell us categorically that climate change has an amplifying effect on hurricanes, floods, tropical storms, forest fires and other extreme weather and increases the odds of worsening droughts. So when we see peoples’ lives being ripped apart by these events on tv, we know it’s because of our fossil fuel consumption. How we frame what is happening is important. I don’t think it’s useful to always be thinking about what we are going to have to give up. We have brilliant innovators and strong communities and we can find a way to live meaningful, loving lives that aren’t in the stranglehold of fossil fuels. I think it’s more useful to acknowledge that by continuing to live high carbon lifestyles we are actively harming other people or taking things away from them: their homes, food supply, sometimes everything, sometimes their lives.

In terms of the whales, of all the life in the ocean that has no voice, I find it helpful to imagine talking to one of my grandchildren, or great grandchildren, someone yet to be born. In my mind I’m describing these benign giants, whose songs reach each other across ocean basins, who are astoundingly beautiful and complex in their societies, who have died out because we couldn’t ditch our cars or slow down or whatever it was going to take. I’m a caretaker and a single mom of three and am not in a position to go and lie down in the road in a climate protest, so I wrote this book instead. I wanted to share my experiences with whales, travelling with them, kissing them even! These magnificent beings who at any given second are filling the ocean around us with song. I hope people can have their own relationships with whales through the book and will want to defend them, defer to them, to show solidarity with them.

PBC: Always drawn to whales and the sea, you navigated on this journey with your small son Max, collecting memories, confidence and meeting amazing individuals along the way. Whales seem to be drawn to you both through the act of singing. Singing was a thread in this book, and it was so intoxicatingly beautiful to imagine these experiences. Bowhead whales sing to each other, you sang to the whales in the Arctic, and you and your son sang to the whales on your journey in the West. How do you think the act of sharing one's voice has on humans and animals alike?

DC: I love this question! It’s got me thinking that there is so much to a voice and to hearing. When I was a small child, I was partially deaf but the hearing tests didn’t pick it up and the doctors didn’t initially believe my mum when she said there was a problem. A doctor recently explained to me that there are different types of hearing tests, including air conduction which tests the outer and middle ear, and bone conduction which tests the inner ear. Soundwaves are vibration, movement, that is carried through the air and into our bodies, so when someone speaks or sings to you, their voice is touching you, and creating movement inside you. I find it impossible to feel alone when I think about that: the birds singing, the insects chirruping, leaves rustling, the whole world and the sea full of song, the vibrations of life travelling around and through us. Whales’ hearing and vocal abilities are astounding. So even though I couldn’t hear the grays vocalise, to connect with them by singing, to see them respond to our voices was unforgettable.

PBC: As you went on this quest, tracking the migrating whales with your young son, you also looked back at a time you journeyed to the Arctic to collect research on climate change and fell in love. While staying with a local family, you experienced their culture hunting whales and learned words from their language, even meeting one of your life loves. Do you think intertwining these stories–one appreciating the culture that comes from an extensive line of whalers and the other tracking them with your son connecting with the sea and these giant sentient beings–is that of the same thread?

DC: Yes, in more than one way. A hunter, Billy, said something to me during my trip to the Arctic in 2006 which sowed the seed for the second trip, even though I didn’t even register what he’d said at the time. Also, looking back at both trips, I saw a connection between so many of my experiences and realised my life-story carried multiple threads of the climate story: climate denial; false balance and the failure of the media; the story of the whales and the ocean and climate; and the structural racism inherent in climate change, the need for climate justice.

The journey following the gray whale migration was an obvious backbone for a book, if only I could write it well enough! It was a huge challenge and exhausting fitting in the editing around being a caretaker during the pandemic but once I’d realised the book might carry those issues to more people than might ordinarily read about them, writing it didn’t feel like a choice. I’m a very private person and I’m very exposed in Soundings but I felt compelled to give everything I had to the book.

PBC: Throughout the book you continually question your capabilities as a mother. “The journey was supposed to help me start anew. It distracted me for a while. But now that it’s ending I’m confronted by all I ran from, a list of my failings. I failed to set up a life for us that I could tolerate, failed to earn enough money to support us, failed to just get on with it like everyone else.” Looking back at this younger version of yourself, do you have sympathy for these feelings of inadequacy? Seeing your son today, does it give that woman solace to know that you have given your son such a precious gift in his early years?

DC: When I look back at that younger me, I feel a lot of sympathy because I see how things were stacked against her. Society makes it difficult for single mothers. They are not valued, not paid. I became homeless, was living in a hostel and using foodbanks. It was very stark. And it’s not getting any easier for those in that position. I hope the book might accompany and strengthen anyone who is going through difficulty, if it makes one person feel less alone then it’s worth it. We can be strong in community. And our community extends to the non-human.

So yes, that journey will always be a source of strength for my family; the relationship with the whales as well as the unexpected support and encouragement from the strangers who became friends along the way. But it is also very painful, given the bond my son and I developed with the grays. I can still see their eyes looking at us when we played with them in the birthing lagoons, can hear the sound of them blowing right next to the boat and spraying us all over with their shrimpy breath. I’m remembering all they do for their young calves, the extraordinary migration from the Mexican birthing lagoons to the Arctic feeding grounds. At the same time I am reading about grays washing up dead on the beaches. It could be those same whales. It’s unbearably sad.

PBC: After closing your memoir, it struck me that it was a book of hope, of adventure but also of deep grief for your lost love and for the whales being impacted by humans, whether it be climate or commercial whaling. Do you think writing this book was necessary in your grief journey? Do you still have hope for the whales and waters of the future and that humans will finally see their impact?

DC: I’m happy that you mention the grief because it’s a hard emotion to manage alone and I wanted people to feel accompanied in their grief. I think it’s such an important emotion, and evidence of our connections. And despite the pain of grief, or perhaps because of it, there’s hope. We know about the impact we’re having now, but our action isn’t proportionate. It’s hard to look the reality in the face, much easier to believe the deniers or look away. But if we can support each other with the difficult emotions, like grief, fear and anger, then I think we’ll be more powerful in our actions and better at helping the most vulnerable.

PBC: I have to admit there were several moments while reading this book I found myself crying. From what you dealt with right after giving birth to your son to losing your life love (I have gone through this myself), to the beauty that you showed through the relationships of whales to their young and also to people. I cannot tell you enough how powerful this book is and how much it has impacted me. You also speak to motherhood. You touch on the impact your own strained relationship with your mother had on you, you feeling out motherhood, and comparing motherhood to whale motherhood. Can you speak to what you learned about relationships in your life and while writing this book?

DC: I’m so moved to hear that you feel so deeply about the stories in the book. My mother was dealing with significant trauma which impacted her mothering and had been passed down through the generations. The mothers in that family were tough, they had to be given the lives they had and what was happening in Ireland. The whales have taught me so much about overcoming trauma, gentleness and being a mom. The grays were nearly wiped out by commercial whalers who attacked them in the birthing lagoons in the 1850s. They fought to the death in those lagoons to try and protect their calves and the surviving whales continued to be aggressive towards boats until a local fisherman, Francisco Mayoral, Pachico, developed a relationship with some of them in the ‘70s. This led to the phenomenon known as ‘The Friendlies,’ where whales approach the boats. Despite that horrific history with humans, they were so playful with us. They saved me emotionally, gave me the strength to rebuild a more loving life for myself and my son. It’s an astonishing privilege to be a mom, to be in the world with the whale mothers and to be able to learn from them. I’m convinced we need those relationships with non-human beings.

PBC: Things I learned about whales: they sing to each other, their tales are like thumb prints and all unique, their final demise descent is called a whale fall.....swoon. What other films, books or otherwise would you recommend to whale lovers?

DC: Oh dear this could be a long list! I’ll limit myself to the Arctic region and here are just a few I’ve found helpful and one I am about to start. If I widen it out beyond that I’ll be here until next week.

- When the Whales Leave by Yuri Rytkheu

- Nunamiut Unipkaaŋich/Nunamiut Stories. Told by Elijah Kakinya and Simon Paneak. Collected by Helge Ingstad, edited and translated by Knut Bergsland

- The Whales, They Give Themselves: Conversations with Harry Brower, Sr. Edited by Karen Brewer

- Whale Snow by Debby Dahl Edwardson, Annie Patterson (Illustrator)

- Floating Coast, An Environmental History of the Bering Strait by Bathsheba Demuth. I haven’t yet got to this one but Dr Demuth’s essay in Granta is a must-read. https://granta.com/on-mistaking-whales-bathsheba-demuth/

- Where the Sea Breaks Its Back by Corey Ford (not about whales but about Alaska)

- Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez

- The Bowhead Whale: Balaena mysticetus: Biology and Human Interactions. Editors: J.C. George, J.G.M. Thewissen

-

The Oceanic Society Field Guide to the Gray Whale. I picked this one up during the journey following the gray whale migration and the cover picture is beautiful.

PBC: Do you have any projects you are currently working on, whale related or literary? Or environmentally as well? Do you plan on visiting the whales soon?

DC: I haven’t flown for years now, and I’d like not to unless it’s absolutely necessary, but I dream that one day I might get across the Atlantic on a boat with the children and somehow visit the Kaleaks again. It’s just not the same on the phone! Whales can be spotted off the coast of Ireland and Scotland so that’s an option I suppose. The grey whales, I just don’t know. I think about them all the time. I used to dream about them a lot, that they were in the harbours, too close to shore. But since writing the book I haven’t dreamt about them. My younger children are pretty envious that their older brother has touched a baby whale and sung to one. They can be very persuasive and I am easily persuaded where whales are concerned so we’ll see… In terms of future projects, there’s a lot of work to do on climate and climate justice. I want to be involved in making change happen and sometimes I just want to just run away into the forest. I’m never sure which one will win out!

About the Author

Doreen Cunningham is an Irish-British writer born in Wales. After studying engineering Doreen worked briefly in climate-related research at the Natural Environment Research Council and in storm modeling at Newcastle University before turning to journalism. She worked for the BBC World Service variously as an international news presenter, reporter, and editor for twenty years. She won the RSL Giles St Aubyn Award 2020 and was shortlisted for the Eccles Centre and Hay Festival Writers Award 2021 for Soundings, her first book.

Doreen Cunningham is an Irish-British writer born in Wales. After studying engineering Doreen worked briefly in climate-related research at the Natural Environment Research Council and in storm modeling at Newcastle University before turning to journalism. She worked for the BBC World Service variously as an international news presenter, reporter, and editor for twenty years. She won the RSL Giles St Aubyn Award 2020 and was shortlisted for the Eccles Centre and Hay Festival Writers Award 2021 for Soundings, her first book.

About Soundings: Journeys in the Company of Whales

In this memoir of motherhood, love, and resilience, a woman and her toddler son follow the grey whale migration from Mexico to northernmost Alaska.

In this memoir of motherhood, love, and resilience, a woman and her toddler son follow the grey whale migration from Mexico to northernmost Alaska.

In this striking blend of nature writing, whale science, and memoir, Doreen Cunningham interweaves two stories: tracking the extraordinary northward migration of the grey whales with a mischievous toddler in tow and living with an Iñupiaq family in Alaska seven years earlier. Throughout the journey she explores the stories of the whales and their young calves—their history, their habits, and their attempts to survive the changes humans have brought to the ocean.

Cunningham’s voice is powerful: sharp, profound, sensitive, and unflinching. A story of courage and resilience, Soundings is about the migrating whales and all we can learn from them as they mother, adapt, and endure, their lives interrupted and threatened by global warming. It is also a riveting journey onto the Arctic Sea ice and into the changing world of Indigenous whale hunters, where Doreen becomes immersed in the ancient values of the Iñupiaq whale hunt and falls in love. For this is Doreen’s story, too—a fierce, feminist tale, touching on her childhood and her time living in a Women’s Refuge with her baby, becoming a mother, just like the whales.

Lyrical, brave, and fearlessly honest, Soundings is an unforgettable journey.