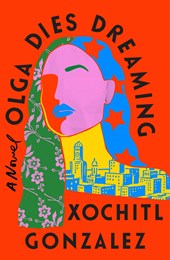

Olga Dies Dreaming

January 27, 2022

Xochitl Gonzalez’s debut novel is as much romantic comedy as it is a search for a balanced personal and political manifesto.

Olga Dies Dreaming by Xochitl Gonzalez, Flatiron Books

(Contains minor spoilers)

One of the first newly published books of 2022, Olga Dies Dreaming is a triathlete of a novel—ambitious, nimble, and protean in its delivery and message. I’m very pleased to share a birthday with this book.

Xochitl Gonzalez’s debut novel is as much romantic comedy as it is a search for a balanced personal and political manifesto. It’s a satire on the lives of the rich-and-TV-famous and a search for identity between races, languages, and family members, near and far. And, with all this going on, it’s a well-written rollercoaster ride toward an unknowable ending.

The story is set up like a rom com—a professionally successful wedding planner in New York City doesn’t want to be tied down by a relationship but seeks something fulfilling beyond her career and the monetary aspects of the American Dream. However, you’ll be alerted to the seriousness of the narrative twice before the story even begins. A laconic statement found in the epigraph, that "The price of Imperialism is lives" by Juan González, one of the founders of the New York chapter of The Young Lords, in conjunction with the disheartening brusqueness of the book title itself, makes one feel like reading this story will become more arduous than the introduction to Olga makes it seem. But the contradictions between expectation and reality for the story and its characters continue, most effectively so.

The narration alternates focus between Olga and Prieto Acevedo, Puerto Rican siblings who grew up in Brooklyn’s Sunset Park. Their estranged mother, a radical activist for Puerto Rico, becomes a third voice to the story, appearing through letters she wrote to Olga and Prieto after she fled the country. Her own children don’t know where she is, since she travels around while still somehow keeping tabs on her family affairs. Though her letters of concern for her children are somewhat sweet, just for the fact that she bothered to write them at all, they are also often unsupportive of her children's own paths. From the perspective of the reader—from one step removed of the messy situations of family, community, and self—all three of these Acevedos are running at the same problem of inequality from different angles, which seems an effective way to make progress. Yet, the three are almost continuously at odds.

Olga has moved onward and upward (literally)—she lives in a high-rise in northwestern Brooklyn and, at 40 years old, has a well-established wedding planning business where she makes good money (and only occasionally steals excess napkins) from upper-class people with high expectations but even higher bank account numbers. As Olga puts it: “I fully support those on the bottom taking as much advantage of the top as humanly possible.”

Prieto, not much older than Olga, is a congressman who believes that inserting himself in the system that their mother fights so strongly against is the best way to assert the importance of and protect their community. And at one point, their mother admits he is right.

After a marriage he used to hide his homosexuality ended in divorce, he moved back in with his grandmother in Sunset Park. While he’s still closeted to protect his machismo among his body politic, he is soon blackmailed by real estate developers who seek to gentrify his neighborhood. And beyond this, he also voted yes on the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA), an unpopular decision in the eyes of his mother and many others who saw it as a “private sector money grab” that hurts more than helps Puerto Ricans.

The fourth Acevedo in the nuclear family, Olga and Prieto’s father, returned with PTSD from the Vietnam War and turned to heroin, eventually dying of AIDS when the two were young. With both of their parents out of their lives, the siblings were raised by their maternal grandmother, who, against their mother’s wishes, brought Olga to church every week. This connection between Olga and her grandmother and her ancestors’ traditional religious beliefs is another thread that urges Olga toward a different definition of herself.

Olga is not someone who would willingly submit to being a puppet of any sort. She learned her lesson early on about the dangers of seeking fame as a person of color in the USA after she was almost a reality TV host, coerced and edited into a stereotyped fiery Latina version of herself for a show about wedding planning. Yet, like many people of color in America, both Olga and Prieto are in a tug-of-war match with their family, their culture, and their own desires. But what skews it all is the American sociopolitical order.

While she and her brother strive for professional success and to make progress for themselves and the Black and brown people who exist subordinately in American politics and society, they both must fight who they are expected to be in order to attain self-worth and work outwards to accomplish more for their Puerto Rican community.

As shown through both Olga and her brother Prieto’s experiences, non-white Americans start on the outside looking in and, even if they step in close enough to appear to be in the limelight, many will never recognize their lives as a true part of American life. But this inability to assimilate can allot more energy and power to a community to change the world around them.

The author’s love for Brooklyn manifests in the vivid scenes of the boisterous and heartfelt interactions in the siblings’ Puerto Rican neighborhood, which transport me to a New York or a community I wish I could know, a vibrant and inclusive and very much alive addition to the American Dream. And among the book’s many characters and histories, Gonzalez’s savvy storytelling keeps me invested and somehow hopeful that Olga will not literally die dreaming.