The Language of Loss is the Language of Life

March 20, 2017

Facing the loss of life requires a new kind of language, one that isn't secret, but shared.

Years ago, I wrote a brief review of Barbara Ehrenreich's Bright-Sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking Has Undermined America, a book that challenges what Ehrenreich believes is our country's habituated sense of optimism. The inspiration for the book was Ehrenreich's experience of being diagnosed and treated for breast cancer which brings with it, for better or for worse, a membership in the club whose members don pink and speak a language of war"journey," "battle," "survivor," "fight,"while touting a kind of enlightenment that comes from persevering through the chemo, hair loss, exhaustion, the waiting, and the fear. The overall point of Ehrenreich's book isn't to mock the glass-half-full crowd, but to offer a different point of view, one that asks whether we need apply American Exceptionalism even to cancer.

Years ago, I wrote a brief review of Barbara Ehrenreich's Bright-Sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking Has Undermined America, a book that challenges what Ehrenreich believes is our country's habituated sense of optimism. The inspiration for the book was Ehrenreich's experience of being diagnosed and treated for breast cancer which brings with it, for better or for worse, a membership in the club whose members don pink and speak a language of war"journey," "battle," "survivor," "fight,"while touting a kind of enlightenment that comes from persevering through the chemo, hair loss, exhaustion, the waiting, and the fear. The overall point of Ehrenreich's book isn't to mock the glass-half-full crowd, but to offer a different point of view, one that asks whether we need apply American Exceptionalism even to cancer.

Back in 2009 when I wrote that article, I didn't have a horse in the race. Since then, cancer has invaded our family in the form of my then 46 year old husband's leukemia diagnosis, stem cell treatment, and recovery. And only through that experience did I come to understand that being diagnosed and treated for cancer is more about submission than anyone wants to confront, and perhaps that's the reason we paper over the experience with well-intentioned war cries and strategy plans. I'm not going to pretend I speak for anyone but myself. I'm not even going to say that I speak for my (very much alive and recovering) husband, whose intimate relationship with cancer and almost-guaranteed death sans treatment is very much his own. But I found, like so many challenges, that cancer requires you to relinquish your control over the result in favor of trusting in the process. Making it through cancer treatment is a group effort, and you, as the patient, as the family member, have little to say in the matter. That doesn't mean that you surrender; it simply means that you allow yourself to ride the waves with the hope of eventually cresting and taking the big one back to shore.

So when I read Amy Krouse Rosenthal's Modern Love essay in The New York Times, You May Want to Marry My Husband, I understood the place she was writing from. No, I've not had to face my own death, as she was, but one way that I coped with my husband's diagnosis was to soberly imagine my life (and my child's life) without him. This wasn't a secret between us. I told him where our son and I would move (a condo by the river), what kind of car I would buy (Mini), and that I would need a nanny (also, dogwalker). Being a practical person who thinks more about the how to do something than the why to do something, he seemed unperturbed by my plans. (Perhaps to sound less villainous, I'll mention here that we've long discussed what he would do should I be the one to die first and it involves him moving back to Minnesota, living on a lake, and marrying a nurse or school teacher.)

Maybe the need to forecast the future in response to a cancer diagnosis is because everything you believed about the present has been destroyed in a matter of minutes. "So many plans instantly went poof," Rosenthal says simply. Or perhaps a matter of seconds. When my husband was hospitalized, immediately hooked up to a (forgive me for the unscientific terminology) blood-cleaning machine due to his high white blood cell count, I overheard one of the technicians mention chemotherapy, as though everyone in the room knew that was a known thing. I left the room and spoke, hesitantly and gracelessly, with the attending physician: "Um, someone in there just said chemotherapy, but, um, as far as I know, he has no diagnosis, so, um, am I missing something?" So I was the one who told my husband--changed the trajectory of his present--, they think it's leukemia. He looked up to his right, his eyes filled, he paused, then looked at me and said, "Well, I'm pretty sure this isn't the thing that's going to kill me." And it didn't.

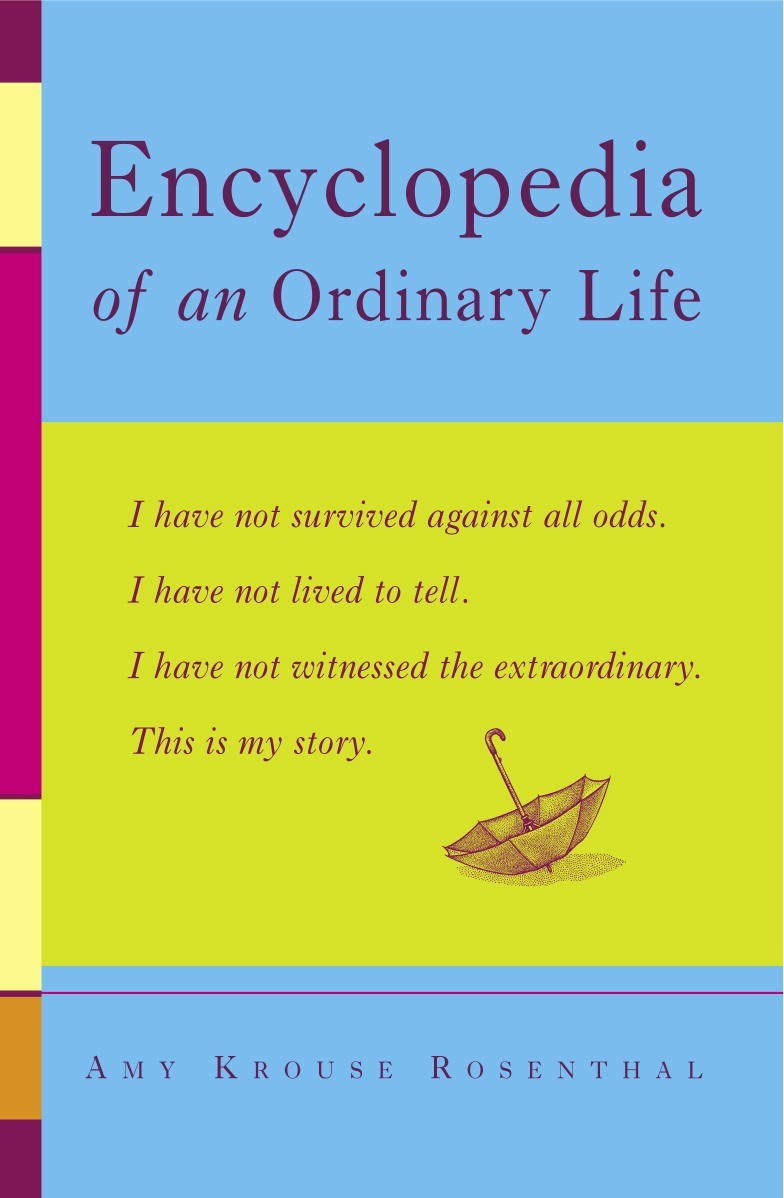

Even after her death, Amy Krouse Rosenthal too is very much alive. I have since purchased her 2005 book, Encyclopedia of an Ordinary Life, and had the pleasure of feeling in conversation with her. (I look for the "good" ones in a bag of potato chips, too!) In it, she writes: "Death is the ultimate nothing." But, in her clever and concise way, she goes on to examine the irony of how much humans fear nothingness only to seek it out in the pursuit of "doing nothing" after a long work week, or on vacation. It is not lost on me that my husband, for the better part of two years, has not been able and/or allowed to do much of anything. The treatment for leukemia involves killing off your immune system, so interacting with the world is a hyper-dangerous risk to take. Even now, when in remission, he continues maintenance treatments that exhaust him and leave him only with enough energy to do nothing. Still, he gets what Rosenthal does not: "more," more time, more life, more of the kind of nothingness that is indeed more than nothing at all.

Even after her death, Amy Krouse Rosenthal too is very much alive. I have since purchased her 2005 book, Encyclopedia of an Ordinary Life, and had the pleasure of feeling in conversation with her. (I look for the "good" ones in a bag of potato chips, too!) In it, she writes: "Death is the ultimate nothing." But, in her clever and concise way, she goes on to examine the irony of how much humans fear nothingness only to seek it out in the pursuit of "doing nothing" after a long work week, or on vacation. It is not lost on me that my husband, for the better part of two years, has not been able and/or allowed to do much of anything. The treatment for leukemia involves killing off your immune system, so interacting with the world is a hyper-dangerous risk to take. Even now, when in remission, he continues maintenance treatments that exhaust him and leave him only with enough energy to do nothing. Still, he gets what Rosenthal does not: "more," more time, more life, more of the kind of nothingness that is indeed more than nothing at all.

I can't tell you whether my husband's optimism saved his life. I'm with Ehrenrich in that I doubt it. I think the specialists, some unknown yet invaluable German stem cell donor, his overall good health, and a bit of luck, did that. But what I do believe is that his optimism buoyed our family. His positivity, despite, for the first time in his life, due to the medical treatments, having to tolerate incapability (always physically and sometimes mentally) kept us all believing that, with time, this too would pass. Not so for Amy Krouse Rosenthal. Time has outlasted her. But the words she wrote, full of good humor and generosity, and yes, optimism for her husband's future without her, will continue to carry her heartbeat into the world, and there are any number of people in that purgatorial place of submission and perseverance, who will be kept afloat by her stirring language of loss.

STATEMENT

“There is so much I want to say. Someone has to say it. It’s never been said before, and it desperately needs to be articulated. As a statement it is at once powerful yet tender, obvious yet insightful; to finally say it is to release a hundred butterflies. But for now, all that surfaces is an unintelligible burst of consonants set to a drumbeat. It will do.”

—Amy Krouse Rosenthal, Encyclopedia of an Ordinary Life