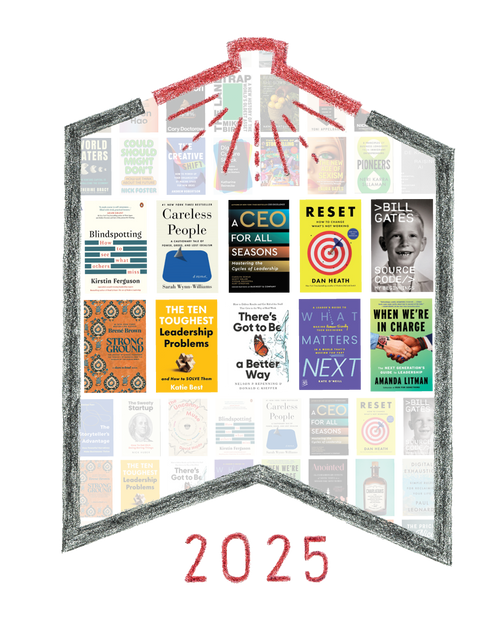

An Excerpt from Could Should Might Don't: How We Think about the Future

An excerpt from Could Should Might Don't by Nick Foster, published by MCD and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Innovation & Creativity category.

You may not know the name Nick Foster. But after just a moment of googling you’ll realize that he’s been shaping the missions of companies that have surely shaped the world you live in—Sony; Nokia; Dyson; Google itself, where he was the head of design at Google X, the search giant’s “moonshot factory”; and the Near Future Laboratory. His insights are unfamiliar because they have been locked behind endless NDAs.

Could Should Might Don’t is Foster’s public debut, the first time a much sought-after explainer of the future is able to tell us how he thinks about the future, how he sees others think about it, and how we might be able to imagine, shape, and make the future better for ourselves. He shows what futurists have gotten wrong and what they’ve done right, and synthesizes years of experience into a clear and inspiring vision not of what to do next but of how to best figure out what to do next.

Foster identifies Could, Should, Might, and Don’t as the four primary attitudes his futurist colleagues take toward envisioning the future. He does not advocate any one of them. Instead, he uses them as lenses to show us where things might have gone if we had been able to think about things differently.

Above all, Could Should Might Don’t is a no-nonsense, practiced, and practical guide to how to think about the future for ourselves—giving us an advantage or two for use in our own lives—and how to make it so.

Could Should Might Don’t has been longlisted in the Innovation & Creativity category of Porchlight Book Company's 2025 Business Books Awards. The excerpt below is adapted from the chapter, "The Metronome Quickens."

◊◊◊◊◊

Let’s assume that a unifying ambition for all humans is the ongoing success of our species. If we can agree on that overarching principle—at the very least—then we clearly, undoubtedly, and undeniably have plenty of work to do. … [T]he pace of change over the last century has been nothing short of breathtaking in almost every measurable respect, and “change” looks set to remain a defining theme of human existence as far ahead as we can see. Technology is hurtling onward at staggering speeds, thrusting its nose into ever more of our business whether we want it to or not. Previously slow-moving and reliably stable natural environments now feel erratic and precarious, and cracks are appearing in a great many of our bedrock convictions about society, culture, governance, and money. Intriguing new ways of thinking are also beginning to emerge that could upend, reprioritize, restructure, and reorder many aspects of the world as we know it. These adjustments could bring about life-changing opportunities for many of our struggling communities or accelerate already problematic levels of division and disparity, depending on how and where they’re deployed. In the coming decades we’re likely to see fundamental shifts in the ways we communicate with one another, in the detection and treatment of illnesses, in how we make things, where we live, how we consume, how we fight, how we entertain ourselves, and how we learn. If we do care about the success of our species, then finding ways to productively think about these things beyond near-term horizons feels like the right thing to do, the responsible thing to do, and the commercially sensible thing to do. The short-term bias that dominated the last century is only now revealing the full spectrum of its impact, and the issues it’s created seem increasingly intractable and difficult to unpick. Given this reality, a shift toward a longer-term, future-oriented mindset, one packed with imagination, creativity, responsibility, and considerations, seems not only useful but essential.

I think most people know this.

But even so, it’s rare that a rigorous, structured orientation toward the future forms the central pillar of our thinking, and it’s almost never integral to the ways in which most organizations, industries, or governments are built. Even given the significant amount of uncertainty we all feel about the future, this kind of consideration remains on the fringes of almost every serious conversation, nudged out of the way by other, more pressing or nearer-term concerns. In any business, the incessant pressure to find clients, balance the books, chase sales, respond to orders, pay debts, ship products, execute plans, and deliver results utterly dominates day-to-day affairs, and many organizations struggle even with these fundamentals. There’s rarely enough time or money available to invest in anything else, so futures work tends to be restricted to only the very wealthiest of companies, and even then, only very occasionally. Likewise, the day-to-day pressures felt by governments—be that shaping headlines, winning votes, defending decisions, or fighting any number of fires—can act as headwinds for long-term thinking. Any consideration for the future is typically relegated to simplistic manifesto slogans or snappy policy statements that are plastered onto podiums, pin badges, and bumper stickers, and whose ambitions rarely extend beyond a single presidential or prime-ministerial term. It seems that democratically elected leaders have become uninterested in embarking on fifty-year transitions or proposing generational investment programs, preferring instead to focus on quick wins and immediate results to capture or keep the attention of voters. Indeed, there’s an uncomfortable reality brewing that long-term political and societal efforts seem increasingly confined to the world’s dynastic autocrats, who have the ambition to undertake such things and are free from the pesky inconvenience of elections and campaigning.

So, when you close your eyes and think about the future, where does all that stuff come from? Surely somebody must be making it. Well, of course they are, in overwhelming quantities, but just as with an all-you-can-eat buffet, quantity doesn’t often equate to quality. A lot of futures work is mistimed, misinformed, imbalanced, willfully shallow, poorly aimed, and sloppily executed, and that’s predominantly due to where and why it was created, and by whom. Our list of future ideas is all but endless, and we all seem to enjoy discussing the merits and pitfalls of individual examples. It seems we’ve become incredibly comfortable discussing and debating the “what” of the future, but I don’t think we spend enough time trying to make sense of how we think about the future, which feels important, especially now. I’ve been interested in exploring these topics for most of my life, and have therefore found successive homes within the bellies of big companies with the time, space, and budget to spend on such efforts. I’ve been involved with thinking about the future of domestic products, from washing machines to electric razors; I’ve explored robotics, prosthetics, and wearable technologies; I’ve worked with teams of people trying to figure out the future of computers and space travel, and have led efforts to tackle some of the planet’s largest challenges, from waste and recycling to energy generation and climate change. These projects have been endlessly rewarding, but in reality, it’s hard to say I’ve ever felt like an integral part of the organizations that commissioned them. In my experience, future-focused work has always been cleaved off into some sort of “lab,” “innovation center,” or “workshop,” which is often housed within a separate building, accessible only by a special key card. There are good arguments for separating future-oriented work from the throbbing heart of a business—so that it isn’t dragged down by the gravitational pull of everyday pragmatism, or to protect it from prying eyes—but this habit of “othering” futures work is one that I find increasingly troubling.

[…]

We appear to have largely pigeonholed long-term thought about the future into the folder marked “nonessential.” A fun, optional indulgence for when you have a little spare time or some leftover money. Rather than forming a meaningful central pillar in how organizations think, futures work is almost universally seen as frivolous, superficial, and flimsy. How can it be that we’re surrounded by such momentous change, such technological evolution, such societal upheaval, and such existential complexity, yet our collective ability to generate rational, balanced, detailed ideas about where we’re headed remains so utterly underpowered and underprioritized? The fact that I can listen to award-winning podcasts, read books by Pulitzer-winning authors, open globally renowned magazines and newspapers, watch presentations from CEOs with PhDs, or meet marketing teams with million-dollar budgets and still hear lazy references to flying cars, hoverboards, The Jetsons, and Star Trek is not just embarrassing, it’s a disgrace.

But how could we change this? How could we rethink the world so that a bias toward the future feels not only enticing but essential? How can we make the development of a well-defined perspective on the future feel as commercially important as sales, partnerships, investments, and returns? How can we find ways for companies, governments, and society at large to feel motivated to meaningfully invest in this kind of work, and then act upon it?

It feels as if a key factor in getting to that point is to aim for a significant increase in the quality of our thinking about the future. If futurism continues to feel clichéd, unrealistic, escapist, self-assured, preachy, vacuous, and generally subpar, it’s unlikely that this kind of work will ever attract those in power, but if its output improves, perhaps its audience will grow and the conversation will get richer. I believe the next generation of futures work needs to feel more considered, professional, and grounded. It needs to fit into the ongoing flow of life and embrace its inherent complexity, variability, and ambiguity. It needs to meet the scale of uncertainty it faces with equal amounts of discipline and detail. It has to be actionable, relatable, understandable, empathetic, reasonable, responsible, and engaging.

In a word, it needs to be significantly more rigorous, and this is where you come in.

Excerpted from Could Should Might Don't: How We Think about the Future by Nick Foster, published by MCD. Copyright © 2025 by Nick Foster. All rights reserved.

About the Author

Nick Foster is a designer and futurist based in California. He has worked at the intersection of technology and design within globally recognized organizations, including Google, Sony, Nokia, and Dyson. In 2021, he was awarded the title Royal Designer for Industry in recognition of his significant contributions to this field—the highest accolade for a British designer. For more than a decade he was a partner at the Near Future Laboratory, the seminal futures collective that developed the practice of design fiction. Foster is a visiting professor at London’s Royal College of Art, of which he is a fellow, and he frequently lectures and tutors at colleges and universities across Europe, Asia, and the United States.