An Excerpt from Reset: How to Change What's Not Working

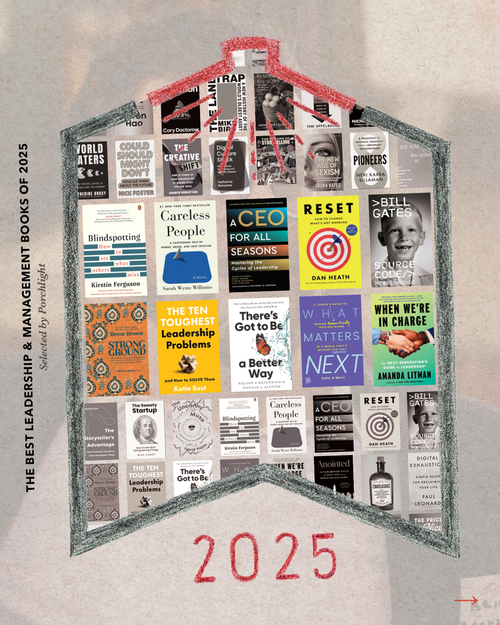

An excerpt from Reset by Dan Heath, published by Avid Reader Press and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Leadership & Management category.

Changing how we work can feel overwhelming. Like trying to budge an enormous boulder. We’re stifled by the gravity of the way we’ve always done things. And we spend so much time fighting fires—and fighting colleagues—that we lack the energy to shift direction.

Changing how we work can feel overwhelming. Like trying to budge an enormous boulder. We’re stifled by the gravity of the way we’ve always done things. And we spend so much time fighting fires—and fighting colleagues—that we lack the energy to shift direction.

But with the right strategy, we can move the boulder. In Reset, Dan Heath explores a framework for getting unstuck and making the changes that matter. The secret is to find “leverage points”: places where a little bit of effort can yield a disproportionate return. Then, we can thoughtfully rearrange our resources to push on those points.

Heath weaves together fascinating examples, ranging from a freakishly effective fast-food drive-thru to a simple trick from couples therapy to an inspirational campaign that saved a million cats.

In Reset, you’ll learn:

- Why the feeling of progress can be your secret weapon in accelerating change

- How leaders can uncover and stop wasteful activities

- Why your team’s motivation is often squandered—and how to avoid that mistake

- How you can jumpstart your change efforts by beginning with a “burst”

The book investigates mysteries: Why the middle is the roughest part of a change effort. Why inefficiency can sometimes accelerate progress. Why getting “buy-in” is the wrong way to think about change.

What if we could unlock forward movement—achieving progress on what matters most—without the need for more resources? The same people, the same assets…but dramatically better results. Yesterday, we were stuck. Today, we reset.

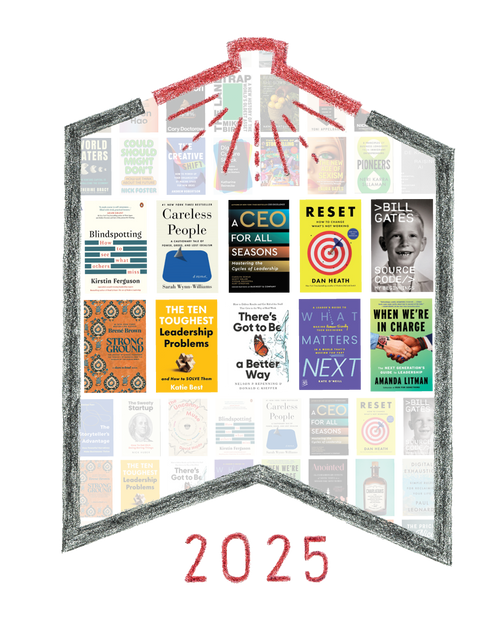

Reset has been longlisted in the Leadership & Management category of Porchlight Book Company's 2025 Business Books Awards. Dan Heath recently allowed us to share the entire first chapter with our readers for a limited time. So, without further ado, here it is…

◊◊◊◊◊

GO AND SEE THE WORK

1.

In 2016, Karen Ritter, an assistant principal at East Leyden High School (near Chicago), wanted to understand how the school could better serve its students. So she chose to do something unorthodox. As part of a program called “Shadow a Student Challenge,” created by the Stanford d.school and the design firm IDEO, she followed around a ninth-grader, Alan, for an entire school day.

Her day with Alan started in PE. She gamely ran sprints in the gym while students gawked and grinned. Afterward, the academic school day began. She sat next to him in class. Completed assignments, just like he did. Ate cafeteria food. (“Lunch was difficult,” she said diplomatically.)

Ritter’s experience was covered by PBS for a news segment, and watching the video of Ritter’s day is a bit like watching a balloon deflate in slow motion. At one point, the journalist asks her how she’s doing. “I’m holding up,” she says with a strained smile. (Body language: I am not holding up.)

Particularly draining was Alan’s algebra class. Because of his low test scores in math, he’d been slotted into a double-length remedial period. The camera caught Ritter sneaking looks at the clock, just like a real student. After a long stretch of instruction, the bell rang, but to Ritter’s chagrin, it wasn’t for her. There were 30 more minutes to go. “It was brutal to sit through that,” she said.

The day before her observation, Ritter was asked to complete a report card, grading the school on a variety of factors. For “Supportive Environment,” she gave the school an A. Then, after her day of shadowing, she was asked to revisit those marks.

The grade for Supportive Environment stayed an A: She was pleased with what she experienced. But on other factors, the grades deteriorated. Before the day, she’d scored the school a B on this statement: “In this school, students learn actively, creating, questioning, discovering.” After her day as a student, the B cratered to a C-minus.

Similarly, with the grinding double-length algebra class fresh in her mind, her score for “Student Engagement” dropped from a B to a C-plus.

By shadowing a student, Ritter discovered that some of her intuitions had been exactly right. The school really did provide a supportive environment. In other places, though, her intuition had been way off the mark.

She wondered about the double-length math period, for instance. “We don’t have proof that this is improving [students’] learning,” she said. “It’s just making them more miserable.” For Alan, the double-length class had crowded out his real interests. He had wanted to take classes in French and automotive skills, but he couldn’t do both. (Other students were able to pick two electives.)

Ritter’s goal, in shadowing a student, was to look for ways to improve the student experience. Her day with Alan had helped her identify two potential Leverage Points: (1) reconsidering the automatic slotting of students into double-length remedial periods; and (2) encouraging faculty to be more interactive in their classrooms. The school would later act upon both of these ideas: The faculty received professional development in better engaging students, and the school subsequently changed its policy to ensure that every student could have at least one elective. (Previously, some kids who had both a double-reading and a double-math course had no choice at all in their schedule!)

In this section, we’ll explore five methods for identifying Leverage Points. Finding them will require some detective work: Sometimes they are hidden—masked by habits or assumptions. Other times (as we’ll see on the next few pages), they can be quite obvious to anyone who looks. Either way, we have to go looking—and we have to know where to look. The tools in this section will give us five independent ways to conduct the hunt.

What we’re looking for are interventions that are both doable and worth doing. “Doable”: meaning that they are possible in the short term. And “worth doing”: because we aspire to move boulders, not pebbles.

The first method for finding Leverage Points is the one used by Ritter, an approach that Nelson Repenning calls “Go and see the work.”* Repenning is a professor at MIT who studies system dynamics. He told me that of all the principles he’s shared with executives and students over the years, the one that most reliably pays off is: Go and see the work.

Meaning: If you’re a school principal, shadow a student for the day. If you’re a factory manager, follow the production from start to finish. If you’re a consultant, map out the flow of activities on a single client engagement.

“Going and seeing the work” is what the hospital receiving area team did when they began their overhaul: They followed packages through the system, from the delivery dock to their ultimate destinations in the hospital.

One executive, following Repenning’s imperative to see the work, discovered that in his company, there was a woman who diligently maintained a repository of the firm’s engineering documents. She spent long stretches of time printing high-definition color prints and organizing them in a room full of file cabinets.

But there was a digital repository that auto-archived these files. It had existed for years. And word never got back to this poor woman.

“When you go see the work,” wrote Repenning and two colleagues, Don Kieffer and Todd Astor, “if you aren’t embarrassed by what you find, you probably aren’t looking closely enough.”†

______________________

*Repenning’s phrasing is a riff on a well-known operations concept called “going to the gemba,” which originated with Taiichi Ohno, the godfather of the Toyota Production System. “Gemba” comes from a Japanese term meaning the “actual place.”

†Note that this spirit of examination—the genuine desire to get closer to the truth—is the heart of “going and seeing the work.” This is in sharp contrast to the CEO who conducts a stage-managed visit to a factory or field office for the sake of good optics: I am an enlightened leader who enjoys mingling with you common folk!

______________________

Repenning, Kieffer, and Michael Morales published a revealing case study in MIT Sloan Management Review. Morales, the president of a Panama City plant that made corrugated boxes, wanted to understand why his paper losses during production were higher than the industry average. So he went to see the work. And the authors reported what happened next:

Mike left his office and visited the factory floor to watch the work and understand its current design. He quickly observed numerous problems. The paper was often too wide, resulting in extra losses from cutting. In addition, paper rolls were often damaged by the forklifts that moved them . . .

Perhaps most notably, Mike observed that the main corrugator machine stopped at 11:30am. Assuming it was an unplanned outage, Mike rushed to the machine only to learn that the machine was stopped every day at lunch. Stopping and restarting the machine at lunchtime not only decreased productivity but also increased the probability of both damage to paper and mechanical problems. Interestingly, the lunch break turned out to be a response that had been instituted years ago in response to instability in the electric power provided by the local utility—a problem that had been fixed long ago.

Morales’s investigation, then, surfaced some obvious Leverage Points for whittling down paper waste. Within two months, paper losses fell from 21% to 15%, reflecting a savings of $50,000.

Now, your first reaction to this story might be: Well, sure, if you’re doing stuff that’s obviously dumb/wrong, then you can easily fix the dumb/wrong stuff. But be careful: Repenning and Kieffer wrote, “We have discovered similarly ‘obvious’ issues in almost every piece of work we have ever studied . . . .”

Glaring problems are sometimes the legacy of past solutions—improvisations and workarounds. Take the case of the paper plant: As the plant manager, you observe that you’re getting unsteady power to your corrugating machine around lunchtime. It’s not good for efficiency, and it’s not good for the machine itself. So you schedule a shutdown every day to preserve the equipment. That’s proactive and wise. A great short-term solution.

But of course you’ll never get an official announcement from the utility saying, “All Clear!” so the daily shutdown continues. Weeks become months, months become years, and habits become enshrined. Your plant depends on so many habits for its basic functioning that eventually you stop distinguishing them individually, and rather they just collectively become The Way We Do Things. A new employee, learning the ropes, is taught: Every day, at lunchtime, we shut down the corrugating machine.

So what looks like “mismanagement” is often the accidental accretion of outdated habits. And the way you can begin to detect and ultimately erode that accretion is by going and seeing the work. You’ll spot places where you and your team have acclimated to problems—instead of fixing them. Those long-tolerated bad habits are Leverage Points: Correcting them is doable and worth doing.

For knowledge work, this type of observation can be harder. You can trace a corrugated box through a factory. But can you trace, say, the development of a market analysis by a consulting firm?

Yes. For sure, yes. But it’s not as tangible. You will have to make it tangible by mapping out the flow: Okay, for the Kipon Trucking account, we first had the kickoff meeting (two hours), and then we prepared a research plan (six days), which we sent to the client, who returned feedback (two days), and then the engagement manager gave assignments to the five core team members (one day), and then . . .

You’re making the invisible visible. Think whiteboards and markers. How long does each step take? Where does work get stuck or delayed? How do communications ping-pong between the team and the client? In what steps do the greatest leaps forward seem to happen? Protect those. And in what steps do the efforts seem to add little value? Rework or eliminate those.

In short, you can still go and see the work.

The key thing here—and the radical departure from normal, everyday work—is that you are substituting experience for conjecture. Tom Chi, a co-founder of X, the ambitious R & D lab at Google, said that most corporate decisions are made using “guess-a-thons.” People sit around and duel in the land of ideas.

A sample meeting: Ted thinks you should try the Bold Strategy. Marisa hates Ted, so she pushes back on it. Helen, anxious about making decisions, always suggests waiting for more data. Gregg is always a hair’s breadth away from making a strained face and asking How will it affect the CULTURE? (Gregg is everyone’s least favorite part of the culture.)

And on and on it goes. Ultimately, as Chi said in a workshop, “Either the person who is best at arguing or the person with the highest title in the room ends up deciding.” The tragedy, of course, is that when you make decisions that way, you’ve made important decisions based on cognitive vapor.

“Smart people will always come up with smart reasons for their guesses,” said Chi. “But that does not mean that their guesses are not guesses. . . . Because it actually doesn’t matter how much you agree or disagree—if it sounds smart or doesn’t sound smart. The only thing to listen for is: When I hear something, is it a guess or is it a direct experience? If it’s a guess, it needs to be treated a certain way. . . . But if it’s a direct experience, then that’s the stuff we want to make decisions off of.”

Chi’s challenge to us is to get out of the “medium of guesses” and into the medium of reality. When we go and see the work, we stop debating ideas and start discovering them.

2.

Going and seeing the work can be particularly important when things stop working. Your marriage hits a rocky patch. Your sales start drying up. Teachers leave your school faster than you can replace them.

Because when unexpected problems arise in our organizations, it often reveals that we didn’t know as much about our “system” as we thought we did.

On this point, consider a study by the psychologists Leonid Rozenblit and Frank Keil, who asked people to assess how well they understood certain familiar devices. How well do you understand how a zipper works? A flush toilet? People reported moderate levels of understanding. On a seven-point scale, with seven reflecting the highest level of understanding, the average score landed a bit under four.

After the participants scored themselves, Rozenblit and Keil put them to the test: Okay, write out a step-by-step explanation of how the device works, from the first step to the last. Feel free to draw pictures to get your meaning across.

There’s a great YouTube video that brings this study to life. A teenager named Alex Nickel, inspired by the research, asked some teenage peers to explain how a toilet works. Their answers were memorable:

TEEN 1: Well, so there’s a handle, and you flush it, and it goes through some machinery . . .

-------------------

TEEN 2: There’s like pipes going up to the top thing, and then you press the flusher thing, and then the water goes all around and it flushes the gross stuff out . . .

ALEX NICKEL: How does that actually, like, flush it out?

TEEN 2: It goes down a pipe? I don’t know.

--------------------

TEEN 3: Water comes out into the bowl and, like, PUSHES the stuff down . . .

ALEX NICKEL: Can you elaborate on that? Like, the pushing?

TEEN 3: Um, I’m not sure.

To get back to the original study: After the participants had finished their “explanations” of the device, they were asked to rate their understanding of the device for a second time.

Their self-assessments plummeted.

“Nearly all participants showed drops in estimates of what they knew,” wrote Rozenblit and Keil in their 2002 study. The psychologists called this the “illusion of explanatory depth.” As they wrote, “Most people feel they understand the world with far greater detail, coherence, and depth than they really do.” When participants were prodded to produce an explanation, they realized, I know a lot less than I thought.

In another study of this illusion, conducted by Rebecca Lawson and published in Memory and Cognition, people were presented with this skeletal picture of a bicycle frame and asked to add pedals, a chain, and the remaining parts of the frame to the sketch:

(Before you look down, pause. Could you do this exercise correctly? How confident are you?)

One person drew a bike like this. Take a second to analyze what’s wrong here.

One problem: This bike won’t move; the pedals aren’t attached to any moving part of the system. And look how high the pedals are! Are people supposed to pedal with their kneecaps?

Here was another participant’s bike:

At first glance, this looks pretty fancy. Spokes and hand brakes were added, unsolicited, for extra realism! But notice the chain and the frame are connecting both wheels. Which means this bike can’t be turned. It’s a one-way ticket to the emergency room.

Here’s one more point of interest about that last bike: The person who drew it reported that they went cycling most days. (Presumably in a straight line?)

I’m poking fun but let me confess: I had to look up the answer about how a bike works. I’m pretty sure I would have drawn the chain around both wheels, too.

So I’m inclined to empathize with the cyclist. After all, you don’t need to understand the bike to use it effectively! Isn’t a functional understanding sufficient?

The problem comes when we mistake functional understanding for systemic understanding. We think because we can use something, because it operates as we expect, that we understand it. And that’s a problem, because when the bike or the zipper or the toilet stops working, we’re sunk. We realize that underneath our functional level of understanding, there’s nothing.

3.

That sudden awakening is what befalls many businesses just as they are plunged into crisis. Businesses struggle, and their leaders think, It’ll turn around. Just wait a little longer. I’ve run this place for 10 years. We’ve been through hard times.

But then, sometimes, things don’t turn around. And because dramatic action wasn’t taken earlier, when it was a choice, it becomes mandatory. Change or go bankrupt.

In those situations—when a business is in danger of failing—investors or board members might hire a “turnaround consultant.” That’s someone who parachutes into the company, takes over the place, makes a bunch of changes, and then leaves after a few months.

Consider how odd this arrangement is. You might think that if your business was in a pickle, you’d seek advice from someone with turnaround expertise, the way that you might visit a therapist if your marriage was foundering. This isn’t that. This is handing over the reins to a stranger. It’s like letting the therapist move in with your spouse, fix the relationship, then turn it back over to you.*

Despite the dire circumstances involved—businesses on the brink of bankruptcy—turnarounds frequently succeed. We’re used to thinking about organizational change as slow. But, no, in these situations, a company might be rescued—from life support to basic health—in a matter of months.

So let’s think like a turnaround consultant. You’re coming into a company that once was viable and now isn’t. This predicament triggers the shift from functional to systemic understanding (as in the toilet and bike examples above). Things were working, now they aren’t. How do you quickly make sense of what’s wrong and how to fix it?

Turnaround consultants go and see the work.† They walk the halls, they observe the production lines. But because they aren’t experts in the particular business they’re now running, the observation is not enough. They need guidance. So in trying to understand the reality of a business, turnaround artists go straight to the front lines.

“If you really want to know what’s going on in an organization, you always ask the people closest to the customer and closest to the core activity, whether it’s providing a service or making something,” said the turnaround consultant Paul Fioravanti on a podcast.

Jeff Vogelsang, a turnaround consultant with Promontory Point Partners, seconds the approach. “I go to people and say, ‘This is a private conversation. I’m not gonna share anything you say. I’m looking for common themes. I’m looking for your opinions. . . .’

“And they’ll say, ‘I don’t care. I’ll tell you everything. They can fire me.’ Then they’ll puke out everything that has gone on, everything that’s wrong. I’ll write 10 pages of notes, 90% of it turns out to be accurate and 10% is emotional or a personal grudge. . . . Within two weeks, the people who work there will tell you what’s going on, if you’re good at asking open questions and shutting up and letting them ramble.”

______________________

*Could someone start working on BODY turnaround consultants? Just call me when my six-pack is ready.

†Wait, never mind about the “body turnaround” thing . . .

______________________

As a methodology, this could not be simpler: To find out what’s going on in your organization, talk to the people who make it run. Here’s what customers really think of us. Here’s why our plant is so messed up. Here’s why the software updates are always late.

There’s no black magic. It’s just listening.

Parenthetically, when I’ve shared this idea with people, I sometimes get a polarized reaction. Some people have a cynical attitude: Frontline people are just clock-punchers. If I ask them what’s wrong, they’re gonna say they work too hard or they don’t get paid enough. And others have an overly romantic view: Yes, power to the front lines! They do all the hard work and nobody listens to them! They could run the place better than the suits!

I sometimes wonder whether either group (cynical or romantic) has actually met any frontline people. Because the truth is, they’re just people. They have smart ideas and dumb ideas. The advice is not: Consult them because they’re wise, selfless oracles. The advice is: Consult them because they know their jobs better than you, and their jobs are closer to reality than yours.

Going and seeing the work, ultimately, is about observation and consultation.

I see we turn off the corrugating machine every day. Why do we do that?

We thought we were helping students with a double-length remedial math course, but is there any proof it’s working? Or are we just doubling their suffering?

The payoff for this observational effort can be profound. Imagine if you could locate and stop the dumbest things your team is doing: the ill-advised, the pointless, the self-sabotaging—BOOM, gone. What would that be worth?

There are unmistakable areas for improvement that we may never see and brilliant ideas for change that we’ll never unlock unless we go and see the work.

Excerpted from Reset: How to Change What's Not Working by Dan Heath, published by Avid Reader Press. Copyright © 2025 by Dan Heath. All rights reserved.

About the Author

Dan Heath is the #1 New York Times bestselling coauthor/author of six books, including Made to Stick, Switch, and The Power of Moments. His books have sold over four million copies worldwide and been translated into thirty-five languages. Dan also hosts the award-winning podcast What It’s Like to Be…, which explores what it’s like to walk in the shoes of people from different professions (a mystery novelist, a cattle rancher, a forensic accountant, and more). A graduate of the University of Texas at Austin and Harvard Business School, he lives in Durham, North Carolina.