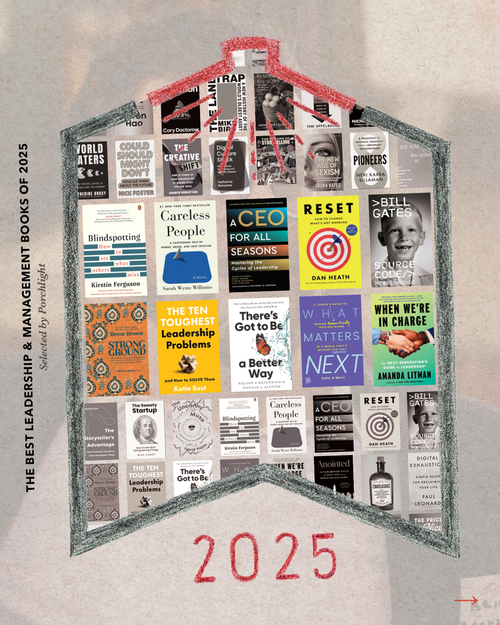

An Excerpt from Bad Company: Private Equity and the Death of the American Dream

An excerpt from Bad Company by Megan Greenwell, published by Dey Street Books and longlisted for the 2025 Porchlight Business Book Awards in the Current Events & Public Affairs category.

Private equity runs our country, yet few Americans have any idea how ingrained it is in their lives. Private equity controls our hospitals, daycare centers, supermarket chains, voting machine manufacturers, local newspapers, nursing home operators, fertility clinics, and prisons. The industry even manages highways, municipal water systems, fire departments, emergency medical services, and owns a growing swath of commercial and residential real estate.

Private equity runs our country, yet few Americans have any idea how ingrained it is in their lives. Private equity controls our hospitals, daycare centers, supermarket chains, voting machine manufacturers, local newspapers, nursing home operators, fertility clinics, and prisons. The industry even manages highways, municipal water systems, fire departments, emergency medical services, and owns a growing swath of commercial and residential real estate.

Private equity executives, meanwhile, are not only among the wealthiest people in American society, but have grown to become modern-day barons with outsized influence on our politics and legislation. CEOs of firms like Blackstone, Carlyle, KKR, and Apollo are rewarded with seats in the Senate and on the boards of the country’s most august institutions; meanwhile, entire communities are hollowed out as a result of their buyouts. Workers lose their jobs. Communities lose their institutions. Only private equity wins.

Acclaimed journalist Megan Greenwell’s Bad Company unearths the hidden story of private equity by examining the lives of four American workers that were devastated as private equity upended their employers and communities: a Toys R Us floor supervisor, a rural doctor, a local newspaper journalist, and an affordable housing organizer. Taken together, their individual experiences also pull back the curtain on a much larger project: how private equity reshaped the American economy to serve its own interests, creating a new class of billionaires while stripping ordinary people of their livelihoods, their health care, their homes, and their sense of security.

In the tradition of deeply human reportage like Matthew Desmond’s Evicted, Megan Greenwell pulls back the curtain on shadowy multibillion dollar private equity firms, telling a larger story about how private equity is reshaping the economy, disrupting communities, and hollowing out the very idea of the American dream itself. Timely and masterfully told, Bad Company is a forceful rebuke of America’s most consequential, yet least understood economic forces.

Bad Company has been longlisted in the Current Events & Public Affairs category of Porchlight Book Company's 2025 Business Books Awards. The excerpt below comes from the book's Introduction.

◊◊◊◊◊

Until it cost me my dream job, i had never given private equity much thought.

When a Boston-based private equity firm called Great Hill Partners bought Deadspin, the digital sports magazine where I was editor in chief, and its sister sites in 2019, it hardly seemed like the worst possible outcome. Our company’s previous owner, Spanish-language broadcaster Univision, had mostly operated the company through benign neglect, never interfering in our coverage but not trying particularly hard to boost profits, which meant the sites punched far above their weight journalistically, yet were losing a reported $20 million a year. Great Hill Partners, though, had invested in trendy, successful brands like Wayfair, Bombas, and the RealReal. The firm’s partners said their goal was to shore up the business side of our company, bringing in more revenue from ads and e-commerce and subscriptions. My colleagues and I wanted our publications to make money. If these finance guys were going to bolster our finances, we’d get to continue producing deep investigations and funny blogs. A win-win.

I had a vague sense that private equity had caused trouble in other industries; the downfall of Toys R Us had been a global news story just a year before, and Alden Global Capital had become the bogeyman of local newspapers. But everyone knew the retail industry was sinking under Amazon’s weight, and that newspapers had sabotaged themselves by failing to adapt to the internet age. We weren’t a failing company: More than 20 million people read Deadspin every month, many of them multiple times a day. I knew private equity was a problem. I just thought it wasn’t my problem.

It didn’t take long to realize how wrong I was.

At first, I couldn’t figure out why none of my new bosses’ ideas seemed like they were designed to serve our large, almost disturbingly loyal existing audience, even though large and loyal audiences are generally considered the holy grail for media companies. They told experienced product managers that quality-assurance testing and other best practices were unnecessary because they cost too much money, which meant things broke constantly. They forbade Deadspin from publishing several types of stories that were among our most popular, then got angry at me when I pointed out that eliminating popular stories would mean fewer readers. They were so busy micromanaging how the company’s journalists worked— not just what stories we reported but what we wore and during what hours we were sitting at our desks— that they never seemed to have time to follow through on their goals for the business side.

After I read yet another story about yet another newspaper driven into the ground by Alden Global Capital, it finally dawned on me that the disconnect I was seeing wasn’t accidental. Alden was destroying newspapers because they didn’t care about newspapers, and because they could make money off their ashes. Similarly, Great Hill Partners did not care about Deadspin. The firm’s goal was never to make our website better or grow its readership. Great Hill Partners, and private equity at large, exist solely to make money for shareholders, no matter what that means for the companies it owns.

In the simplest terms, “private equity” describes a system in which a firm bundles money from outside investors— including university endowments, public pension funds, state- owned investment funds, and ultrawealthy individuals— which it uses to buy and operate companies. The firm and the investors have a symbiotic relationship: the firm gets to use the investors’ cash for its own business goals, while the investors earn returns when portfolio companies are sold or taken public. Sometimes the way to make the most money involves strengthening the portfolio company itself. But even then, the benefit is only incidental, its success a mere side effect of increasing profits for the private equity firm and its investors.

And often, making money for the firm and its investors doesn’t even require making money for the portfolio company. Private equity firms earn management fees, transaction fees, and monitoring fees that typical companies do not. They benefit from tax breaks that allow them to keep much more of their profits than other types of businesses. They can sell a company’s assets and pocket the proceeds rather than reinvesting them. There are stunningly few limits to the methods a private equity firm can use to profit off a company it owns, whether or not the company profits too. Even the company going out of business entirely can be lucrative for its private equity owner.

In other words, the point of Deadspin wasn’t to make money for Deadspin. It was to use Deadspin to make money for Great Hill Partners and its investors. Shareholder value is the only measure of success.

By that standard, Great Hill Partners is thriving. While it does not release detailed information about its financial performance, it did boast about ranking tenth on a list of the midsize private equity firms that generate the best performance for investors in 2019, the year it bought Deadspin’s parent company.

Three months after Great Hill took over, I submitted my resignation, explaining that my bosses’ micromanaging what we published was hurting our traffic and making it impossible for me to develop a coherent editorial strategy or lead my staff effectively. Two months after that, following another showdown with management over what they were allowed to write about, the rest of the staff followed me out the door. Great Hill attempted to rebuild the newsroom, but the audience had disappeared. In 2024, the firm sold Deadspin to a Maltese gambling company, which now uses the site to drive traffic to online casinos. In less than five years, Great Hill’s executives had turned one of the most popular sports sites on the internet into one that draws slightly less traffic than a Pennsylvania dog breeder called greenfieldpuppies.com.

Great Hill Partners itself avoided any fallout from the Deadspin debacle. In 2024, the year it sold the site, its partners announced, it rose to number four on the list of the midsize private equity firms that generate the best performance for investors.

Excerpted from Bad Company: Private Equity and the Death of the American Dream by Megan Greenwell, published by Dey Street Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 2025 by Megan Greenwell. All rights reserved.

About the Author

Megan Greenwell is a journalist who has written or edited for publications including The New York Times, The Washington Post, New York Magazine, WIRED, and ESPN. She is also the deputy director of the Princeton Summer Journalism Program, a workshop and college access initiative for students from low-income backgrounds. A California native, she lives in Brooklyn with her husband and their pug.