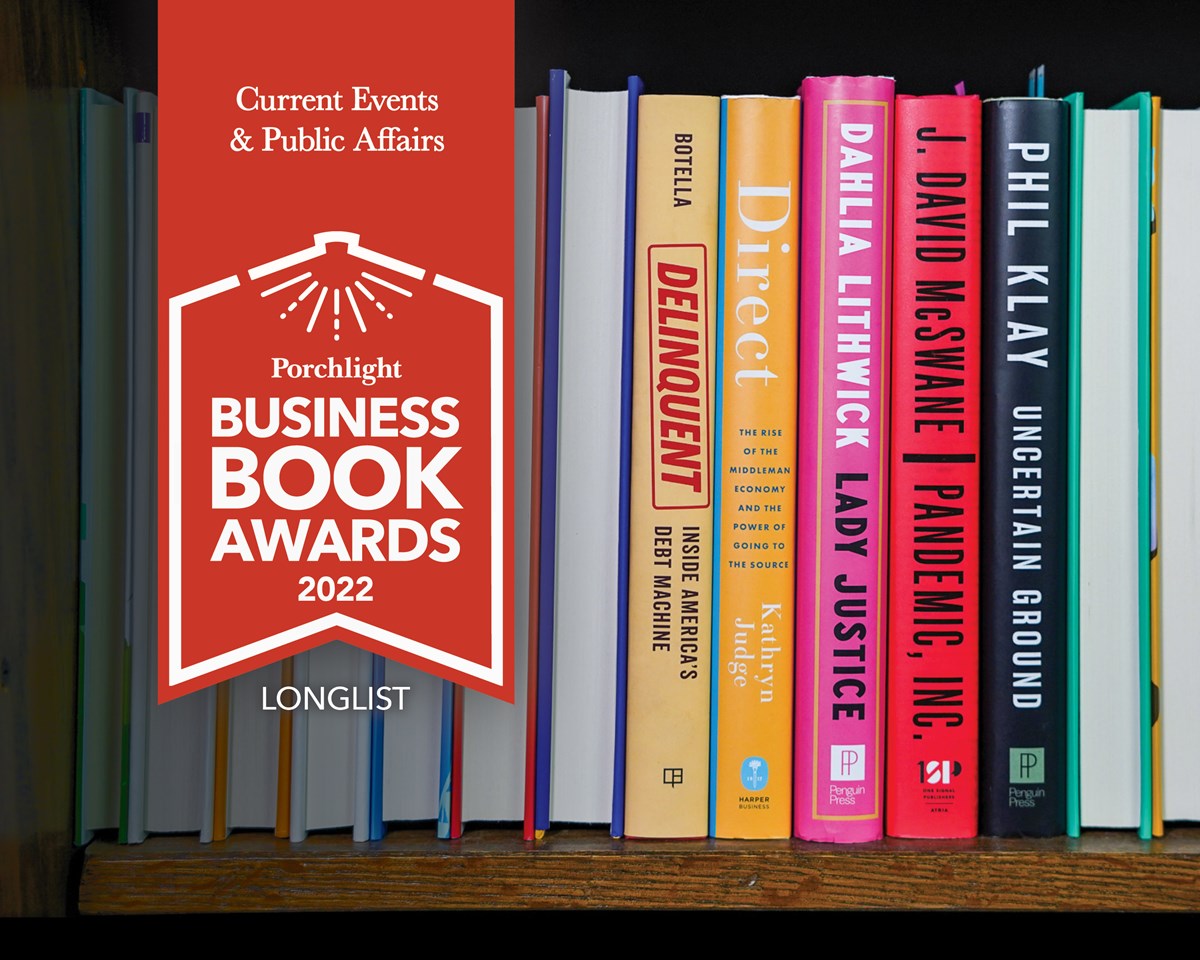

Inside the 2022 Longlist | Current Events & Public Affairs

November 29, 2022

It seems like each and every category of our awards has elements of Current Events & Public Affairs percolating within them, but that doesn't negate the need for a dedicated category. These are the five best books in that space this year.

The world has been upended by Big Tech, the pandemic, and political instability. Because of that, every single category of our awards has elements of Current Events & Public Affairs included in it. After all, how does one consider Leadership & Strategy without understanding what's happening in the wider world their organization exists in? How does one look at Management & Workplace Culture, and go about hiring and managing people when the inequality and inequities of our society have been laid bare before us and we know we are not removed from the responsibility to address it? How does one approach Marketing & Sales when the social media platforms that we've conducted much of that work on become engines for misinformation and havens for hate speech? Our Big Ideas & New Perspectives category was basically a forum for technologists and futurists not too long ago. This year, there are two university presidents exposing what they’ve found fundamentally broken in the academic world and other more arcane institutions at the heart of American life.

Turning to the books actually submitted in the purview of Current Events & Public Affairs, we meet a woman who worked in the upper echelons of the credit card industry before becoming troubled by its business model (increasingly, our economic model) and looking for one that is more humane. We meet the lawyers who stepped up to meet the challenge Trumpism posed to our democratic norms. We learn about how middlemen came to dominate our economy with increased efficiency and reduced friction, and why we might want to add more friction—direct contact with the people and companies who produce the products we buy—back into our lives. We peer back once more at the height of the pandemic and how badly it was mismanaged, learning about some of those who profiteered off the pain. We process the costs of war—on one war fighter, on the military community, on our nation, and on those in the countries where we've waged them—and the costs of collective inattention to the wars being fought in our names. There is a lot that we'll find broken, but what it all points to is a more humane and less technocratic way of conducting business—even if it is the business of war—and a more caring country and economy.

Delinquent: Inside America's Debt Machine by Elena Botella, University of California Press

Delinquent: Inside America's Debt Machine by Elena Botella, University of California Press

Income inequality has been written about ad nauseam, but we should keep on talking and reading about it. What Elena Botella teaches us is that inequality is not only exacerbated by, but is in many ways created by, how credit functions in our economy. She eschews the typical talking points of both the left and the right for a more nuanced view that most people, in most cases, are simply taking on too much debt. And the current system is set up in such a way that people don’t have much of a choice in the matter. Botella exposes the marketing schemes that banks (and bank-like fintech startups) use to tempt poor Americans to take on more debt, and how their indebtedness fuels the investment gains of others.

Botella, after working in the industry and getting to know it intimately, firmly states that “it should be completely clear by now that that the problem with the debt machine was never a few bugs in the system. It was the system itself.” She also show how profiteering off the indebtedness of poor Americans is strangling innovation and growth in the broader economy. And, unlike many books about systemic problems, Botella doesn’t just call these problems out, but imagines “a system of credit in which every loan granted made the borrower’s life better.” Even if you are tired of hearing about it, or think you know everything about the root causes of income inequality and how it might be addressed, I urge you to pick up Elena Botella's Delinquent. It is an unexpected eye-opener and page-turner.

Direct: The Rise of the Middleman Economy and the Power of Going to the Source by Kathryn Judge, Harper Business

Direct: The Rise of the Middleman Economy and the Power of Going to the Source by Kathryn Judge, Harper Business

While we seem to relish the convenience and nearly frictionless commerce offered by middlemen today, we once understood that the presence of middlemen came with significant (sometimes criminal) costs. Those are largely hidden from us now, but the rise of a middleman economy affects our daily lives, the work we do, the way we buy, and the very structure of the society we live in. Yes, the rise of middlemen like Walmart and Amazon ostensibly saves us time and money, but the irony at the heart of the neoliberal order we live in today is that “people today do not seem to enjoy the extra wealth and leisure that are supposed to follow from saving money and time.” There are many reasons for that, but the main one is that the always low prices they offer don’t really save us money in the end because they know how to shape our behavior to ensure that we buy more than we originally intended to or really need, with real consequences:

Expanding waistlines and exploding closets may seem trivial relative to the racial wealth gap and financial fragility. Yet recognizing that so many different ills can be traced, at least in part, back to the middleman economy is key to understanding just how much is at stake in decisions about “through whom” to buy and invest.

But there is hope. The technologies used to create the middleman economy can also be used as tools to go direct to the source. Judge details where progress has been made on that front, and how it has been a decidedly mixed bag with some bad actors and moral failures of its own, and concludes with a final chapter detailing “Five Principles for Policy Makers, Companies, and the Rest of Us” to use to be more conscious and deliberate in the choices we’re making.

There was a time when middlemen were thought of more as profiteers than proficient managers of supply chains, which brings us to...

Pandemic, Inc.: Chasing the Capitalists and Thieves Who Got Rich While We Got Sick by J. David McSwane, One Signal Publishers

Pandemic, Inc.: Chasing the Capitalists and Thieves Who Got Rich While We Got Sick by J. David McSwane, One Signal Publishers

If there could be a better test case than a global pandemic for when and where an unfettered free market might fail us, I can’t think of one. But it wasn’t a free market failure alone. As David McSwane writes, “COVID-19 would render in high definition the contrasts of an inequitable nation. At the same time families waited in miles-long lines for groceries at food banks, the pandemic economy created about 500 new billionaires.” At least 40 of those 500 were minted due to “the boom in biotech and healthcare stocks” in “companies that gained from COVID-19.”

But both the failures and the successes—business and moral—were fueled proactively by government policies. A staggering amount of fraud was perpetrated against, as easily as it pointed in the right direction by, programs to relieve the suffering caused by an economy that was put on pause overnight. The stock market soared as local economies sputtered and people suffered. As the absurdity of conspiracy theories proliferated, so did unscrupulous profiteers who promised much-needed supplies that they couldn’t deliver and state governments battled each other (and sometime the federal government) to be first in line for what they needed. Even the successes in developing vaccines in record time were funded by the taxpayer money that funded much of the research, and bought up the entire supply of vaccines to distribute it more efficiently and equitably than market forces ever could or would. By the time vaccines arrived, ignorance and disinformation had been peddled alongside snake oil remedies (or in this case, actual horse medicine) to such a degree that people refused to get the jab. So the battle to end the pandemic was lost early on, and was blown again after a brief comeback late in the game. The human cost has been, and continues to be, staggering.

I'd urge anyone who wants a fuller understanding of what went down to pick up Pandemic, Inc. But it seems most of us just want to ignore it and move on. As our next book demonstrates, we have had ample practice at that over the past 20 years.

Uncertain Ground: Citizenship in an Age of Endless, Invisible War by Phil Klay, Penguin Press

Uncertain Ground: Citizenship in an Age of Endless, Invisible War by Phil Klay, Penguin Press

America’s presence in Afghanistan (mostly) ended this year. Whatever one wants to say about that two-decade conflict, or the one waged in Iraq over those same years, one thing we can’t say is “we won.” And the responsibility for that doesn’t fall on the American soldier, but on the American people as a whole, who turned their attention away from the work our soldiers were doing. And, of course, it falls on our elected representatives who allowed the expansion of those wars without providing a mandate for them or defining what victory looked like. As Phil Klay writes in his new collection of essays from over the years:

The founders of the republic originally wanted to force Congress to vote every two years just to keep a standing army; these days Congress won’t even permit a vote to replace the Authorization for the Use of Military Force that was passed prior to the Iraq War and that we are now using to justify fighting against groups that didn’t even exist back then.

Some of the pieces that moved me most profoundly in Uncertain Ground were those that are deeply personal in nature. At the end of his essay on “Tales of War and Redemption,” Klay writes of how “being responsive to suffering and attuned to joy are not different things, but one and the same.” But I believe they'll resonate with an entire nation. Like Tim O’Brien did for the generation that fought in Vietnam in The Things They Carried and Jospeh Heller did for the generation that lived through World War II with Catch-22, Klay’s fiction has given American citizens a look at the realities and absurdities of war being fought in our names today. This collection of nonfiction does the same. We cheer for military flyovers at football games, but we have little idea what our military is doing abroad. “So,” writes Klay, “while America chooses to express its love for its military in gooey, substance-free displays, our military waits, perhaps hopelessly, for a coherent national policy that takes the country’s wars seriously.”

Yes, America may have wound down its presence in Afghanistan this year, but the wars our soldiers are fighting are not over. We owe it to them to pay attention, and to restore and renew the sense of purpose for which they fight.

Lady Justice: Women, the Law, and the Battle to Save America by Dahlia Lithwick, Penguin Press

Lady Justice: Women, the Law, and the Battle to Save America by Dahlia Lithwick, Penguin Press

Slate’s senior legal correspondent Dahlia Lithwick is one of the sharpest observers of the law in the United States. Her new book about the legal work women did during the years of the Trump presidency provides an understanding and context with contemporary breadth, historical depth, and a delightfully dry wit to keep things from becoming too depressing—which it easily could in other hands.

Lithwick lives in Charlottesville, Virginia, so she was literally on the ground when Nazis invaded and terrorized that city in 2017, injuring scores of counterprotesters and taking the life of Heather Heyer in the process. The “near-total breakdown of government and institutions that day” in Charlottesville was a black eye not only on Virginia, but on the country, and it was amplified and further inflamed by the then-president’s utterings of “fine people on both sides.” But then attorney Robbie Kaplan arrived and got to work uncovering the full scope of the horrors of that day and documenting the deliberate plans neo-Nazis and other hate groups had been making online that led to it. It is scary stuff, mostly swept under the rug or shirked off as “legitimate public discourse” since—a la the January 6th insurrection at the U.S. Capitol—and it is just one of many frightening challenges Trumpism posed to democratic and institutional norms, many of which have been attacks on women’s rights. “But women are not without legal and constitutional resources to fight back,” writes Lithwick, “Female lawyers know this fight intimately; they’ve been doing this work for decades.”

Lady Justice details just how much of this work they’ve taken up in the last six years and how successful they’ve been in that work. It is not a straight line, as this year’s reversal of Roe makes plain, but Lithwick leaves us with hope this crucial battle can be won.